Why school lunches mean so much to Munjama and her friends

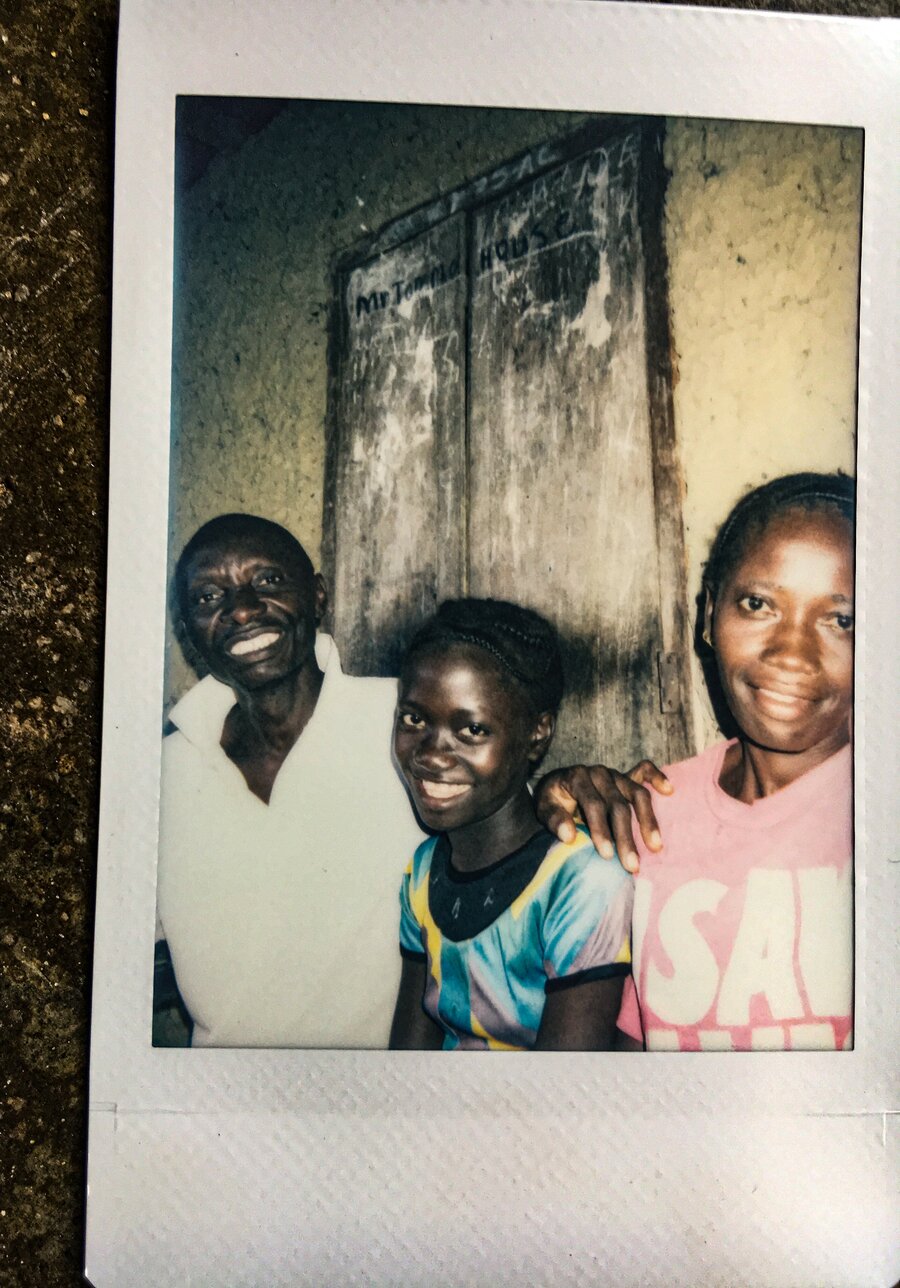

Munjama Toma, like most 11 year olds, loves nothing more than to play with her friends and go to school.

Also like her friends, she has aspirations for her future, explaining: "I want to be a nurse when I grow up."

Living with her mother, father and eight other siblings in rural Sierra Leone, she has been brought up around adults with little to no education, and a dependency on the land that leaves many households vulnerable to poverty.

She is also faced with the reality of being a girl in a country where gender inequality is systemic and child marriage is prevalent.

‘To be in school is my dream.'

Hoping for a better future, she knows that her dreams lie in the classroom. However making sure children like Munjama are encouraged by their parents to attend is critical. "To be in school is my dream," says Munjama.

Extreme poverty is high in rural parts of Sierra Leone. Pujehun District has the highest rate of poverty nationally, with one in three families deemed food insecure. In the small village of Helebu, where Munjama and her family live, the majority of families are involved in small-scale farming which provides a low income for poor families.

While communal rice fields have increased production in recent years through support from government and partners including the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP), food is still not an abundant resource. Families face the annual lean season, or ‘hungry period', without enough food.

"I have a big family. Sometimes I cannot afford to feed them all."

Under these conditions, any sort of shock — from sickness to a price increase in the local market— has a marked effect. Almost immediately the daily food ration is cut and children's nutrition especially suffers as a result. The district has one of the highest rates of stunting in the country, currently standing at 38 percent.

"I have a big family, eight children. Sometimes I cannot afford to feed them all, and before when there was school fees I struggled to send them," says Munjama's father Amara.

With continued hardship come more drastic measures, with education being cut short or early marriages arranged to reduce the number of mouths to feed. In this context it is often the youngest girls of the family that are most vulnerable, with the premium put on boys by society.

"I never went to school, because we had no money. Instead I was taught petty trading and married at 15," says Mariama Swaray , a mother of five and neighbour to Munjama's family.

"Back then people did not see the value in the girl child. Education was not seen as important for women."

With their education brought to a shuddering halt, these young girls are immediately placed at a disadvantage to the rest of society, conditioned to a life of early child rearing and domestic work. Any dreams of leading a better life are instantly quashed as the reality of being a young, uneducated mother quickly sets in.

School feeding — namely a daily hot meal during school time — ensures vital nutrition for vulnerable girls through their childhood and adolescence, and provides an incentive for families to send their daughters to school rather than them being forced into work or an early marriage.

In 2018, with support from the governments of Canada and Japan, WFP relaunched its school feeding programme in two of the most food-insecure districts of Sierra Leone — Pujehun and Kambia. In the first year of the pilot, WFP reached more than 29,000 children with nutritious school meals, of whom over 14,000 were girls.

"The meal at school helps me manage many mouths to feed."

Community reaction to the pilot has been positive. Local mother-support groups have rallied behind, either providing additional nutritious foods to strengthen school menus, like leafy green vegetables, or establishing school gardens to grow their own.

While the meal itself is not designed to substitute home-cooked dishes, for many large families like Munjama's it becomes a lifeline as they would struggle otherwise to provide regular, nutritious food. The value of a school meal is equivalent to about 10 percent of a household's income and helps dads like Amara manage other household pressures.

The seeds of change can also be noted among the men of the community, with education of girls increasingly being viewed as an investment for the entire family.

"I would like my daughter to be a nurse so she can support the family," says Amara. "Neither myself nor my wives are educated. I do not want her to lead a life in the field. If she is a professional she can support the family better. The meal at school helps me manage many mouths to feed."

On a nutritional level, the meals are also supporting healthy growth among children, offering a regular source of nutrients that are essential for their mental and physical development.

"The families are providing fish and vegetables to make the dishes better for the children. When the children come for their meals I can see they are happy and each day they get stronger," says Jenneh Jalloh, a cook at Munjama's school.

Teachers are reporting an overall increase in attendance and improved performance of the children.

"Before school feeding, some of these children would only have one meal a day in the evening and keep a portion of that left over for the morning. Now the children have two meals a day and their attention is increased," says Augustine Fallay, deputy headteacher at Helebu Primary School, which Munjama attends.

As the school holidays come to an end and the new school year steadily approaches, Munjama is committed to continuing her education.

Having more education than most adults in the community, these girls are already pushing the boundaries of gender empowerment. The power is most definitely on the plate when its comes to keeping girls at the table of education.