WFP in 2020: Conflict, climate change, coronavirus and the Nobel Peace Prize... in pictures

January

The World Food Programme marks the 2010 Haiti Earthquake anniversary—on 12 January that year, up to 300,000 people were killed following the magnitude 7.0 quake which struck at 4:53 p.m. Within 30 seconds, a world turned upside down. With more than a million displaced, tens of thousands risked going hungry.

WFP is currently scaling up its emergency programmes to reach 900,000 of the most vulnerable people in the country of 11 million, 4 million of whom require emergency food assistance. The organization is appealing for US$4.4.million to sustain assistance in Haiti through 2021.

February

City-sized swarms of desert locusts destroy crops across East Africa. South Sudan is among the countries experiencing invasions on a scale not seen since the 2003–05 infestation in West Africa.

In addition to the locust invasions, South Sudan has been facing worsening hunger and food insecurity due to torrential rains, extensive flooding and conflict. WFP is currently delivering food to remote, insecure and difficult-to-access areas. Since June, it has provided food assistance to nearly 973,000 people in flood-affected areas. The organization needs nearly US$475 million in the coming year.

March

As commercial airlines stop flying at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, WFP steps in to fill the void, working closely with the World Health Organization, to ensure the continuity of the humanitarian and health response.

Personnel form nearly 200 aid organizations, such as the International Committee of the Red Cross, are transported to vulnerable locations, with personal protective equipment and other medical supplies in tow, as WFP's Common Services sets up Global Humanitarian Response Hubs in critical locations.

April

Almost 1.6 billion children and youths in 197 countries are missing school as classes are suspended to restrain the spread of coronavirus. Some 370 million are no longer receiving school meals — in many cases the only meals they can count on.

And as schools begin to close, WFP steps in to make sure schoolchildren continue to receive meals. The organization has six decades of experience supporting school feeding and health initiatives which help children learn and perform better, broadening educational opportunities.

WFP also launches a partnership with UNICEF to support efforts to ensure school-based nutrition and health services will be offered as incentives for the most vulnerable children to return to school once the emergency is over. In place of school meals, governments and WFP provide take-home rations, vouchers or cash transfers to children in 68 countries.

School meals are especially critical for girls. In many poor countries, the promise of a meal can be enough to make struggling parents send their daughter to school, allowing her to escape heavy domestic duties or early marriage.

May

Makoko, in Lagos, Nigeria, the world's largest floating slum, is often referred to as the ‘Venice of Africa'. Here, the Nigerian Government is reaching out to vulnerable urban areas, with technical advice from WFP.

Nigeria is Africa's biggest economy and, with 182 million people, the continent's most populous country. In Nigeria's North East, a combination of escalating conflict, displacement and disruption to livelihoods could spell a hunger catastrophe for millions. Without sustained humanitarian assistance in the areas most affected by the crisis in Borno, Adamawa and Yobe states, 5.1 million people could struggle to feed themselves during the June-August lean season.

June

The world's Indigenous peoples face unprecedented health and economic challenges because of COVID-19 and associated restrictions. Nearly three times as likely to live in extreme poverty as their non-Indigenous counterparts, the 476 million people who identify as Indigenous —6 percent of the world's population—have historically experienced extreme levels of socioeconomic marginalization, discrimination and political exclusion.

In many countries, indigenous people turn to ancestral traditions to respond to the pandemic. These include reviving old food customs as certain vegetables become unavailable, as well as tapping into Indigenous knowledge to develop hand-sanitizers using plants and fruits, and to alleviate symptoms.

While some communities are able to survive on local resources, for others it is not as easy, so WFP steps up to provide food baskets to the most vulnerable. It donates seeds to smallholder farmers, provides take-home rations to schoolchildren and delivers face masks, gloves and disinfectants to community leaders for distribution to health centres and individuals.

July

Already suffering the world's biggest humanitarian crisis, and with its healthcare system in tatters, Yemen has seen its problems further exacerbated by COVID-19.

Access continues to pose a serious challenge to WFP in several areas, especially where conflict is intense. Despite security challenges, WFP and its partners manage to deliver assistance to nearly 13 million people in the country.

August

The Beirut port blast on 4 August kills more than 200 people, injuring more than 6,000.

The loss of the port casts a shadow on food security in a country already beset by the worst economic crisis in recent years. Not only do most of food imports, on which Lebanon depends for 85 percent of its needs, transit via Beirut port, but the explosion has destroyed 120,000 metric tons of grains stocked there.

Even before the explosion, food security in Lebanon was a cause of serious concern, with one million people living below the poverty line and 45 percent of the population sliding into poverty. WFP worked around the clock to provide immediate relief to those directly affected by the blast through the delivery of food parcels containing rice, pasta, bulgur, chickpeas, oil, salt and sugar.

September

Although Pakistan has become a food surplus country and a major producer of wheat which it distributes to vulnerable populations, the average household has to spend half of its monthly income on food. This makes families particularly vulnerable to shocks resulting in high food prices. Just as in many parts of the world, climate change makes things worse.

This year, heavy monsoons caused fatal flooding across Pakistan, which displaced tens of thousands of civilians and wiped out nearly one million acres of crops. WFP provides cash and food assistance, working to facilitate long-term solutions such as water harvesting systems in areas affected by droughts or floods, or where displaced people are returning.

For WFP, working to prevent, mitigate and prepare for disasters is an essential part of its mandate to save and change lives.

October

After almost a decade of conflict, families across Syria are facing growing levels of poverty and food insecurity. Severe humanitarian needs persist across the country as the price of basic foods has increased by an astonishing 247 percent in the past year alone, sending 9.3 million people into food insecurity.

WFP's school meals programme in Aleppo employs vulnerable women and provides them with training and an income so they can support their families and become financially independent.

November

A humanitarian crisis starts building up on the Ethiopia-Sudan border as 100,000 people flee their homes in the Tigray Region of northern Ethiopia due to conflict. The violence triggers a massive wave of displacement, putting thousands at risk of hunger — peace is vital to stop the situation worsening.

In Sudan, WFP has been providing high energy biscuits, hot meals and monthly rations to feed 60,000 people in camps, though additional funding is urgently needed.

December

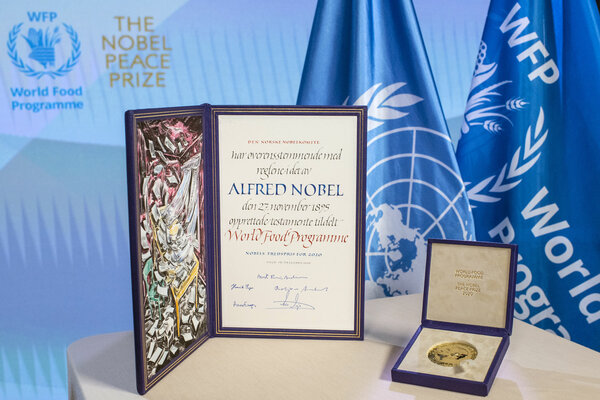

In a ceremony in Rome on 10 December, WFP receives the 2020 Nobel Peace Prize medal which it was awarded in October in recognition of the link between conflict and hunger, and the critical role that food assistance plays as a first step towards peace and stability.

Executive Director David Beasley received the Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of the agency and its 20,000 staff during a virtual ceremony watched by thousands of viewers. "This Nobel Peace Prize is more than a thank you," he said. "It is a call to action. Because of so many wars, climate change, the widespread use of hunger as a political and military weapon, and a global health pandemic that makes all of that exponentially worse —270 million people are marching toward starvation."

As we end 2020 and look to the future, we remain inspired by our colleagues, partners and the people we serve — and determined to come together to achieve zero hunger.