War in Ukraine: No safe harbour

On my first day in Ukraine’s historic Black Sea port city of Odesa, missiles were launched from the Caspian Sea. They flew some 1500 kilometres before blasting through the first and second floors of an apartment building a few blocks from the hotel hosting me and my colleagues from the World Food Programme (WFP). The missile strike was reported to have injured 18 people and killed a grandmother, her daughter, and baby granddaughter. The baby’s father had gone out to buy some milk, only to find three generations of his family wiped out when he returned.

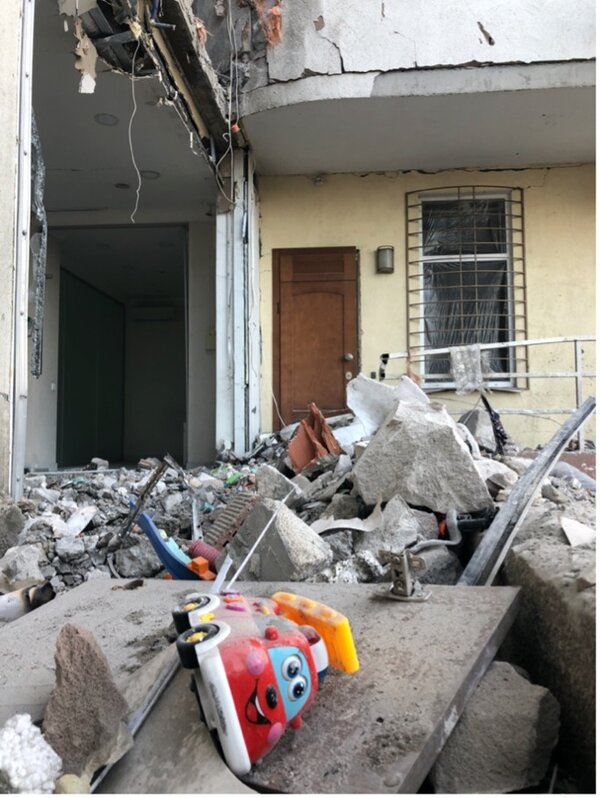

Two days later, burnt cars and trees still smouldered, while workers shovelled debris from the gaping hole of the building into piles below. Other crews were already stacking bricks for repairs. I spotted some family photos and a child's toy firetruck in the debris…remnants from ruined lives.

Several times during the day, and frequently in the middle of the night, air-raid alarms sound a warning to people to shelter. Odesans, known to be rebellious and curmudgeonly, have begun ignoring the alerts, seemingly in spite.

War in Ukraine: 'We left everything and ran for our lives'

Piles of white sacks block roads and protect buildings near the historic Potemkin steps and by monuments to Pushkin and Catherine the Great. The bags are similar to those used by WFP around the world but, rather than being filled with wheat or beans as the printing on them suggests, they are instead filled with sand. Meanwhile, tons of food are stuck in the port of Odesa. That’s the tragic irony of this conflict: Russia and Ukraine supply 30 percent of the world’s wheat supply. But due to the military blockade, wheat, corn and sunflower oil overflow silos and ships stuck in Black Sea ports.

In the farm fields that have not been turned into battlefields, seeds are being planted for the next harvest which starts in June. But where will it go? If the food currently held in silos in the port of Odesa and others cannot find its way out, Ukrainian farmers won’t have a place to store the next harvest. Tons of food will be wasted while millions of people across the world will face starvation. To be precise, 44 million people, according to the latest WFP assessment.

Almost a third of the Ukrainian population is now displaced or living as refugees in other countries. WFP has provided food assistance to almost 3.6 million people. The biggest challenge is reaching those who haven’t been able to leave besieged or cut-off areas. Many are elderly – too frail or ill to flee.

Ukrainians are not the only ones affected by the conflict. Currently, half of the wheat WFP needs is stuck inside silos and in ships blocked in port, while millions of hungry people in places such as Yemen, Ethiopia, Syria, and Afghanistan are suffering the consequences of the blockade.

That’s why it is essential that food being produced in the war-torn country can flow freely to the rest of the world before the current global hunger crisis spins out of control. The ripple effects of the conflict on food prices will impact WFP in two ways: It will cost more to buy food and the number of people needing food assistance will increase.

At a WFP food distribution site in a church, I met Alexis, a sailor who fled the fighting with his family from Khersen. While waiting to get a WFP box with pasta, canned meat, rice, oil, and salt, he told me how frustrating it was for him to be landlocked, unemployed, and registering for food rations, when he should be out on the seas helping feed the world with food that filled the ships stuck in port just a few kilometres away.

There is a saying: “Ships in harbour are safe…but that’s not what ships are built for.” Until the fighting stops there won’t be much smooth sailing anywhere in the Black Sea.

Jonathan Dumont is Head of Emergency Communications at the World Food Programme