‘Technology in emergencies gives us the bigger picture. It helps us find solutions.’

This week marks one year since the start of the Rohingya refugee emergency. Pedro Matos, a Programme Officer for the World Food Programme (WFP) in Bangladesh, explains how his team harnesses technology even in difficult environments like Cox's Bazar — home today to nearly 1 million Rohingya refugees. From mapping food insecurity to accessing drone images, technology is providing for a better and faster crisis response.

How does WFP use satellite imagery?

WFP has been making use of satellite imagery for years across vast regions as a way to inform our programmes. For example, we monitor the rainfall patterns across the Sahel to estimate whether rains will arrive earlier or later than predicted and the likelihood of a drought occurring.

What is new in WFP is the operational use of very-high resolution images over small areas for applications such as estimating population in refugee camps, monitoring the impact of our resilience projects (such as water reservoirs or reforestation) in the months and years after they are completed, or receiving images from satellites quickly after they pass over an affected area in order to estimate the number of people in need and whether the roads leading to them are accessible to our food vehicles.

How can maps save lives?

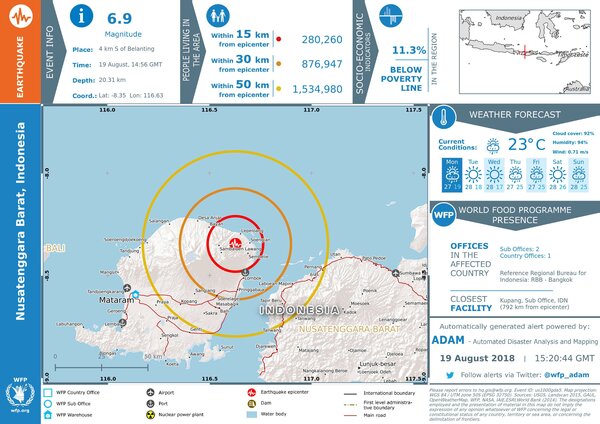

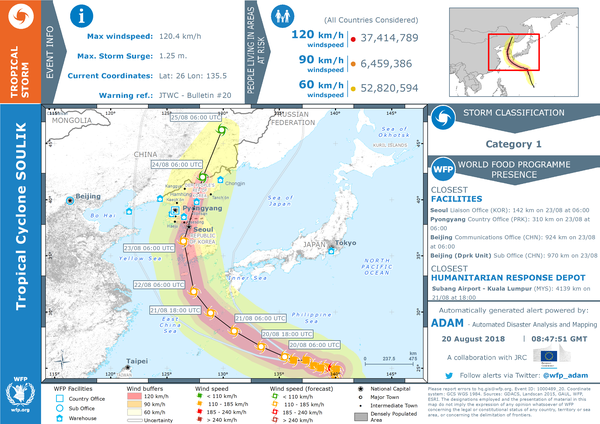

When preparing for emergencies, by improving the information at the disposal of humanitarian organizations so we can direct our plans to relocate people out of harm's way or "pre-position'' food, shelter and other assistance in high risk areas. Satellites also let us detect the onset and extent of a drought much earlier than with conventional means, enabling a timely assessment of the impact of these events on populations and agricultural production. We can then use this in the early planning stage of humanitarian response. Once a disaster hits, satellite-based maps can help assess the severity of a disaster and provide information over large areas where our field monitors would take a long time to cover or can't reach at all.

How can the satellite imagery improve food security?

Having better data on the food security status of communities allows WFP to better design resilience and safety net programmes, maximizing the effect of our interventions. For instance, by using satellite images to map out which communities are most vulnerable to drought, we can design a cash-for-work project to help build a water reservoir. The cash transfer also boosts family incomes and improves the overall food security of that community. We can then use satellites to monitor the impact of that project through time, see which projects work better in a given region, and design increasingly better programmes.

What is your experience with maps?

I actually started my career in the map and space sector. I worked for two space agencies and a number of private space companies before joining WFP 10 years ago. There is a lot of willingness and resources in the space sector to address the planet's problems, while humanitarian agencies have an extensive field presence and a great knowledge of some of the world's most urgent needs but not much expertise in high-tech solutions to solve them. I have been working to merge the two worlds and link the willingness of both sides to develop operational services from satellites that we at WFP can use to address hunger in the world.

When a population is entirely reliant on aid, like in Cox's Bazar, ensuring access remains open even in the worst weather conditions is vital. In the past year, the UN and partners along with the authorities in Bangladesh have installed many kilometers of roads, access ways, footpaths and stairs, and stabilized slopes in what is now the largest refugee camp in the world, home to almost 1 million people. Being able to access satellite and drone images has played a critical part in preventing any major disasters so far despite the ongoing and serious risk of landslides during the monsoon season.

From child birth support, to vital vaccinations programmes, and emergency outreach responses such as during the diphtheria crisis, health services are reaching hundreds of thousands of people in the local communities.

Following on from initial emergency shelter provision, more than 212,000 households — almost the entire refugee population — have now also received shelter upgrade kits to help them cope with some of the worst monsoon conditions in the world. Construction has begun on mid-term shelters, which can withstand stronger winds.

Deep water wells, drainage and latrines have been also constructed, and hundreds of thousands of hygiene kits and water purification tablets have been distributed to help improve access to clean water.

More than 866,000 refugees receive life saving food every month, and more than one quarter of the refugees assisted now have access to food through e-vouchers. These smart cards can be used in allocated shops to buy 18 different food items, including rice, lentils, fresh vegetables, eggs and dried fish, leading to more nutritious and diverse diets.

We are now looking on how to integrate satellite images with artificial intelligence and the aerial images taken from drones that are now used in every major emergency. These technologies are changing the way we think about innovation in the humanitarian world, opening up new exciting possibilities to plan and respond to emergencies across the planet.

Technology in emergencies gives WFP and humanitarian partners the bigger picture. It helps us find solutions to large problems and reach those in need.

It has been nearly a year since hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees fled violence in Myanmar. WFP has been providing life-saving assistance through food distributions and electronic vouchers, and nutritional products for the prevention and treatment of malnutrition. WFP urgently needs US$ 110 million to sustain food assistance to more than 860,000 Rohingya refugees in Cox's Bazar through January 2019.