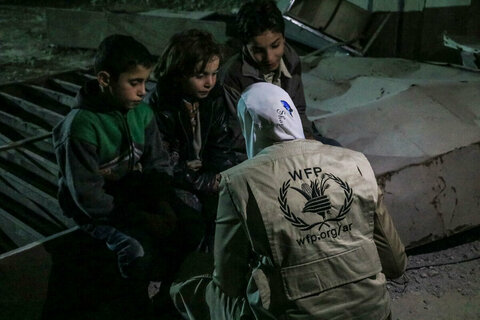

Syria in crisis: Food ration cuts set to plunge millions into severe hunger

Fast-depleting funds are forcing the World Food Programme (WFP) to cut food and cash-for-food assistance for nearly half of the 5.5 million people it supports in Syria, from July. The move is a last resort that will harshly impact up to 2.5 million people dependent on what are already half-rations on which they can barely survive.

WFP’s rising operational costs, in tandem with people’s increasing needs, make maintaining the current level of assistance impossible beyond October – in countries such as Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Chad, Mali, Palestine, Tanzania and Yemen, the organization has also had to introduce drastic reductions.

In Syria, WFP urgently requires a minimum of US$180 million to avert cuts and continue providing food assistance at its current level until the end of the year.

“Instead of scaling up or even keeping pace with increasing needs, we’re facing the bleak scenario of taking assistance away from people, right when they need it the most,” said WFP's country director for Syria, Kenn Crossley.

“Further reductions in ration size are impossible. Our only solution is to reduce the number of recipients. The people we serve have endured the ravages of conflict, fleeing their homes, losing family members and their livelihoods. Without our assistance, their hardships will only intensify.”

Crossley added: “We have the capacity and solutions to reduce dependency on humanitarian assistance and make a lasting difference in people’s lives. It's critical that we keep providing life-saving food assistance to help families get through each week and each month, while we work on interventions that help people rebuild their lives and get back standing on their feet.

“Our partners have been instrumental in preventing such cuts before, particularly over the past two years. Now, we count on them to prevent irreversible harm to the Syrian people’s future. The time to act is now.”

Meet Maher

“We’ve been in a crisis for 12 years – war, displacement, declining economy, I don’t think there has been a similar crisis since the Second World War … living is difficult beyond imagination,” said Maher, at a WFP-backed nutrition clinic in Deir Ezzor.

Maher’s family has been receiving WFP food assistance since 2018 – of his four children, two are malnourished. “We had her bones checked at the hospital,” he said of his daughter, Layan. “The results showed that her growth corresponded to a 5-year-old child – but she’s 10.”

Layan’s teachers say that she has struggled with memory and focus in class. His wife is also malnourished and has anaemia.

“The cuts will affect my children who are already in bad shape, let alone if you take wheat flour, pastries and rice away from them,” said Maher. “Before the crisis, I was an employee at a petroleum facility, but it was destroyed.”

In 2010, his income was around US$400 (20,000 Syrian pounds) a month. Now, he earns only US$14.

Displacement, earthquakes and people on the brink: The conflict in Syria 12 years on

“We should eat three meals a day, but we’ve reduced that to two. We delay breakfast as much as we can and then we have lunch at around 6pm. This way we save one meal,” he said.

“In 2018 and 2019, the WFP ration was substantial. Sometimes it came with beans, macaroni and canned food. It contained more oil (5 litres) and more rice, (10kg),” he said. “But over the past two years, it’s progressively shrunk. We no longer receive macaroni or beans, and the rice and oil have been reduced.”

WFP is deeply concerned about the impact of cuts on families who largely depend on its food assistance. With precious few opportunities to earn cash that might cushion the blow, those removed from assistance will face unimaginable hardship.

Every two months, Maher receives 4 litres of oil, a bag of wheat flour, 4kg of sugar, 4-5kg of rice and a bag of chickpeas.

“My wife rations the food further to expand,” he said. Even so, these supplies last barely a month.

“We try to manage (when there are no rations). We boil potatoes or grill eggplants so that we don’t need oil or ghee. We have to be careful to make it work with what’s available.”

WFP is using vulnerability data to determine who gets prioritized for food assistance. People who get removed from assistance will have the opportunity to appeal.

“It’s difficult to manage our living without assistance,” Maher added. “Even though it’s small, living is difficult without it.”

Beyond immediate humanitarian relief, addressing the needs of the Syrian population will require long-term early recovery interventions and a sustained effort to promote peace and stability.

Since 2015, food insecurity levels in Syria have increased by over 50 percent from 8 to 12.1 million people in 2022 – out of a population of over 20 million. Syria’s conflict-rooted food insecurity has in recent years been exacerbated by global events such as the economic collapse of Lebanon, the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine and February’s earthquakes.

As the Syrian pound falls to record lows, the first quarter of this year saw the price of a standard food basket of essentials rise by 10 percent. This is almost four times the average wage of a schoolteacher.

Meanwhile, WFP staff on the ground report rising anger and frustration among the people we serve, and paint a stark picture of the pressures they face.

“People may resort to having their daughters marry early, or taking their children out of school to work and if I may be honest, women may be abused, forced into sex work or sexually abused,” said one field monitor.

Like many parents, Maher sees little cause for optimism. “Our condition is already bad, so you may imagine how it would look like without food assistance. We wait for the phone call every two months to go and receive the food ration. If this stops, I don’t know what to do.”