Window on Syria: A WFP photographer looks back at a decade of conflict

I have always wanted to write about Syria and the beauty of this country. The history, the old souks [markets], the generosity of its people — it's a country that consists of more than 20 ethnic and religious groups living in harmony as one.

But I find myself writing about my country and my people at the most difficult moments they have ever faced. I‘ve held a camera throughout some of the country’s darkest moments. I have documented suffering while living on the frontlines. I’ve seen fear in my children’s eyes.

For years, this was our daily life, and conflict was the only topic we talked about. Scenes of destruction that would shock anyone became something normal for us. Today, Syrian children are growing up thinking that this is what a city looks like.

When I took the photo above, I wondered what this child was thinking about. What do you see?

Alep, Syrie: “Chaque jour qui vient est pire que le précédent”

What do you imagine happened here? Women and children are always the first to be affected by conflict. Children shouldn’t be exposed to such violent scenes. Unfortunately, after a decade of destruction, a whole generation is now growing up traumatized by what they have seen and heard. For many years, displacement dominated the news about Syria. People fled to save their loved ones, and their own lives.

At that time, I wasn’t sure what to say to someone who had been displaced. Even a simple question such as “How are you?” seemed so out of place. Of course, people who had left everything behind were not OK.

But the people I met during this time always gave me the impression that this would just be a temporary situation. They had lost everything they had, but not their smiles, their spirit and hope. On every mission I joined with WFP I was worried for the people that I met. I thought I’d cause them pain by asking them to share their stories, but they have always given me positive energy and motivated me with the resilience they have shown.

Syria: ‘If it wasn’t for WFP’s airdrops, we would have died’

The most important thing I learned from displaced families during this period was patience, to be a good listener and never give up.

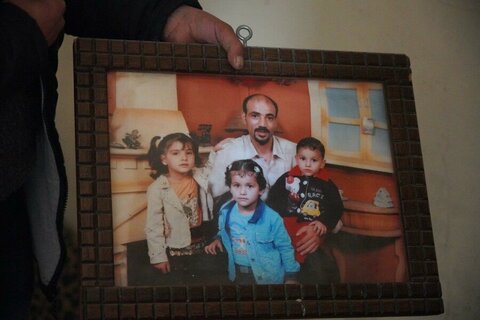

When I met this displaced family, everything was strange for all of us. The family had converted this empty shop into a shelter, and they thought the man with a camera was an odd visitor. I wasn’t confident about what I'd ask, but resident Mohammed’s kindness made me forget this was a shelter and I felt that he was receiving me at his home. He was confident that things soon would soon be better, and that he could then return home.

It is very difficult when someone returns home and finds it has been destroyed. Abo Ahmad’s words are still in my mind many years later. “I will fix it, and even if I can’t, I will come back to my home and live in a tent on top of the ruins and I will still feel like I am home.”

The smell of roasting coffee beans led me to Um Abdallah’s room. Like most of the people I meet, she was displaced and lost her home, but she still kept up her daily habits of making a morning coffee. All she had to offer me that day was a cup of strong Arabian coffee and a smile.

Families left everything — relatives, friends, childhood homes, children’s toys — to escape the conflict and reach a place where they felt safe and peaceful. Their journey wasn’t easy. They slept on stones, faced fear along the way and learned to expect the unexpected.

One of the most tragic moments that I photographed was this child throwing an old shoe into the fire to keep warm. At the time, he had nothing to wear on his feet.

I came across this painting in Al-Hamidieh area in the old city of Homs, after it became accessible. The painting conveyed a strong message that Syrians are like trees. They have roots in this ground, and like the trees they never want to leave their home. It meant a lot to me that people have a connection with this place and with Syria in general.

I felt that after years of conflict, Syrians were ambitious to rebuild and start new businesses and new lives. But when peace arrived in cities across the country, people’s joy didn’t last long. The economic situation began to decline, and families began to realise their struggles were not over.

Towards the end of 2019, I noticed that the topics that people talked about started to change. They now complain about high food prices and ask for support from WFP for the first time. This was something I hadn’t experienced during the crisis previously. During the worst years, people used to ask for non-food items like gas and electricity, but not often for food.

Out of the ten years of the crisis in Syria, 2020 was one of the worst economic years for many reasons: the deteriorating situation in neighbouring Lebanon, the collapse in the value of the Syrian pound and record high food prices meant that there was no end to the suffering. COVID-19 destroyed what was left of the exhausted health system. The 11th year of the crisis looks set to be bleak for citizens across Syria.

Watching food prices soar from day to day has been one of the biggest challenges. No one would believe this could happen in a country like Syria, which once produced enough food for everyone. Today, Syrians queue for bread, fuel and gasoline, and 12.4 million people are unable to put even a basic meal on their tables.

At the start of March, it is very painful for me to see the price of cooking oil skyrocket exponentially. WFP provides families with five bottles of oil in their food ration each month, equivalent to the average salary of 50,000 Syrian pounds per month (around US$12.5 at the black market rate which is used for pricing all commodities in Syria).

I have spent many years working behind the camera lens. I have seen the difference that food from WFP is making to the lives of families who have nothing left to eat. I have asked hundreds of people if they are OK and what they need. Families are no longer smiling when I ask them these questions.

In 2021, Syrians will need our help more than ever. The world must not forget them.

Learn more about WFP's work in Syria