Super resilient, super nutritious superfoods!

They’re good for us. They’re good for the planet. Better yet, they taste good. As consumers worldwide discover or reconnect with superfoods - resilient fruits, vegetables, grains and other plant-based foods - the World Food Programme (WFP) is part of the journey.

From Africa to Asia and Latin America, we’re working with farmers, food processors and consumers to revive old food traditions and introduce new ones. Championing the multiple payoffs of superfoods is all the more important today, in a world threatened by climate change, biodiversity loss and massive hunger.

East Africa’s powerful potatoes

Patricia Loput wants to be a doctor, and thinks potatoes - specifically orange flesh sweet potatoes - will get her there.

“I have learnt so many things at school, including growing sweet potatoes,” says Patricia, 16, who attends Namalu Mixed Primary school, in Uganda’s eastern Karamoja subdistrict. “I plant crops that I can sell to pay my school fees, and buy scholastic and other material.”

Loaded with vitamins and minerals, and drought and disease tolerant, orange flesh sweet potatoes have become a Karamoja wonder crop since WFP introduced them three years ago to one of Uganda’s poorest and driest areas.

“As a food security crop, especially in the lean season, we thought orange flesh sweet potato would be perfect,” says Kennedy Uwuor, who headed WFP’s Karamoja area office. “We also thought it would help tackle malnutrition using locally based foods. And it’s climate resilient - so we ticked that box as well.”

Three years after piloting it, WFP has seen the tuber’s reach extend to more than 200 Karamoja area schools and thousands of families this 2024/25 academic year. Through WFP school demonstration gardens, children learn not only how to grow the plants, but also about the importance of diversified diets. They take home vine cuttings and teach their parents how to cultivate them as well.

“I learned orange flesh sweet potatoes are very nutritious and its leaves are as well,” says school cook and mother Esther Angolere.

Uganda is not the only country where the tuber is blossoming. In southeastern Kenya, WFP supports farmers in growing orange flesh sweet potatoes for schools and local markets. “The orange sweet potato is more profitable than maize,” says Kenyan farmer Mwanaisha Halua. “And we harvest it two to three times a year.”

In Uganda, the school gardens complement WFP’s hot meals programme in Karamoja, which reaches nearly 80 percent of local schools - providing not only a nutritious meal, but also an incentive for kids to stay in school.

“When children are at school, it protects them from early marriage and you learn new things,” student Patricia says.

“In 2021, communities were telling us, ‘pay us’ to grow the sweet potato,” WFP's Uwuor says of Karamoja, where sorghum has traditionally ruled. “Now, you see the orange flesh sweet potato growing organically, and it’s a beautiful transformation.”

India’s ‘millet mothers’

In the eastern Indian village of Singarpur, farmer Subasa Mohanta is known as ‘Millet Mother’ for her success in growing and promoting the hardy, nutritious grains.

“Millet is like goddess Lakshmi,’ says Mohanta, comparing the crop’s bountiful harvest with the Indian deity of wealth and prosperity. “It is three times what I got from paddy,” she adds, comparing her first millet harvest to her previous rice output.

Mohanta counts among more than two hundred thousand millet farmers across India’s Odisha State who have become the first line of defense against hunger and uncertain weather - made more volatile with climate change. Millet’s sturdy stocks flourish in a variety of soils, requiring little water, no fertilizers and a shorter growing period than many other cereals.

And because the protein- and fiber-rich grains can be stored for long periods, they serve as an important 'famine reserve' for many struggling families.

Today, the state-run Odisha Millets Mission is promoting millet’s resurgence in Odisha as a climate-resilient cereal for nutritional security. The WFP-supported effort also aims to inspire similar initiatives in other Indian regions as well as other countries.

“Millet is environmentally friendly and ideal for rain-dependent smallholder farmers,” says Pradnya Paithankar, who heads WFP’s climate change, resilient food systems and disaster risk reduction work in India. “It is indeed the crop of the future.”

“Millet was part of our diets,” says another millet grower, Pabitra, describing earlier days when the grain was eaten especially by pregnant and malnourished women. Like a number of other of the women participating in the millet project, she comes from tribal peoples.

“But people stopped eating it when rice became the leading food and all the farmers grew it,” she adds. "Millet started being seen as the poor people’s food, only eaten when you have nothing.”

Harsher weather and Odisha State’s promotion of the crop have changed mindsets. Today, the ancient grains - many millet varieties exist, all powerful sources of vitamins and minerals - have emerged as a popular superfood in India, one of the world’s leading millet producers.

In Singarpur, farmer Mohanta’s yields have turned her into the area’s go-to millet expert. “People respect me,” she says, “and farmers from far-off villages come to seek advice.”

Bountiful Bolivia

Trigidia Jiménez is an engineer with a mission. In the tiny community of Sunavi, in Bolivia’s southwestern Oruro department, she’s focused on putting cañahua - a hearty traditional grain grown in the country’s highlands - back on the nation’s plates.

“We are revaluing cañahua cultivation to restore it to the Bolivian family food basket to improve the quality of our nutrition,” says Jiménez, a member of the Quechua Indigenous community, of a crop that has been grown in the Andean region for millennia.

Considered a ‘cousin’ to quinoa and bursting with vitamins and minerals like iron and magnesium, cañahua counts among a raft of local and ancestral superfoods WFP is promoting in Bolivia. Not only is the South American nation one of the world’s most biodiverse, but it also has a rich food heritage and a trove of ancestral knowledge.

“Bolivia’s food holds the country’s best-kept secret: its impressive biodiversity,” says Alejandro López Chicheri, WFP Country Director in Bolivia.

WFP's superfoods initiative - which also targets other highly nutritious native crops, including the asaí berry, extracted from wild palm trees, quinoa and chiquitano almonds - aims to reintroduce these resilient, traditional foods into Bolivian diets.

“Bolivia’s different altitudinal features and climates allow it to host over 2,500 varieties of potatoes, over 75 varieties of maize, and over 1,000 varieties of chili peppers,” says Julio Canedo, WFP Bolivia food heritage consultant, offering just a few examples of the country’s amazing bounty.

Traditionally, cañahua grain was husked, roasted and pounded into flour that was added to meat, says agricultural engineer Jiménez. People also boiled the flour with potatoes topped with grated sheep’s cheese. “It is a simple dish to prepare,” Jiménez says, “but very nutritious.”

Ethiopia’s sensational sesame

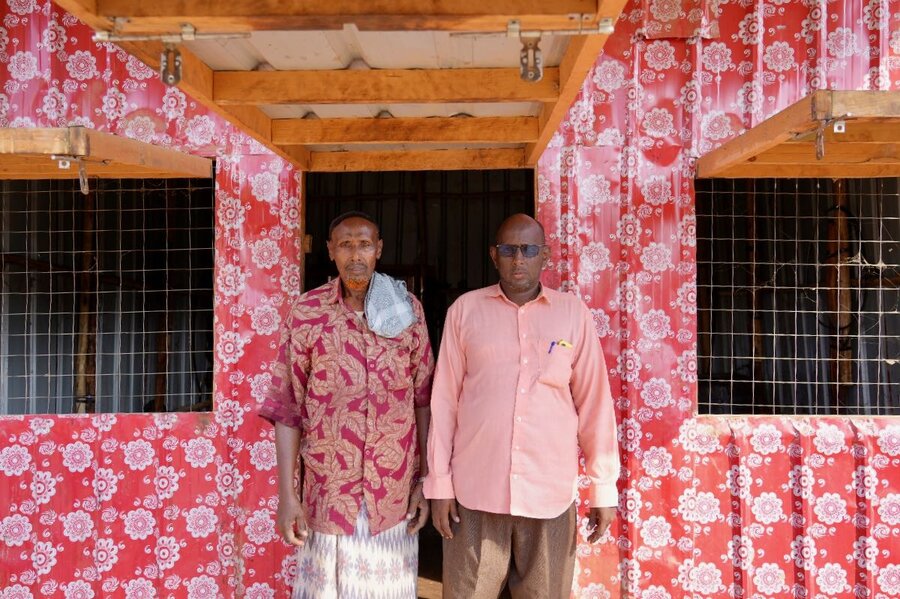

Abdirashid Ali is proud of his sesame seed processor - the first of its kind in the Ethiopian border town of Dollo Ado where he lives. “Our oil travels far, it goes up to Jigjiga (the regional capital) and other regions in Ethiopia,” Ali says, “and even crosses the border into Somalia.”

Run by Ali and his friend and fellow trader Ahmed Ibrahim, in Ethiopia’s southeastern Somali region, the processor is one dividend of a WFP project to boost Ethiopia’s cultivation of the drought-hardy seed that is packed with protein, vitamins and oil. Launched two years ago, the sesame initiative is part of a bigger effort to boost food security and resilience among tens of thousands of Ethiopian farmers and herders amid a drier, changing climate.

Cultivating sesame brings an added value; it’s a valuable cash crop, praised for its rich, nutty flavor. Along with farming support, the WFP project also provides processing machines for some participants - like Ibrahim and Ali, who run a successful cooperative.

“Farmers from all around this area bring their sesame seeds to our shop and we process it into oil,” says Ali. With continued support, he adds, “I believe we can grow into a company that can handle exports of the sesame oil.”

El Salvador’s sturdy sorghum

Hadid Sánchez remembers drinking atol as a little girl, a sweet breakfast beverage that her mother made with sorghum. Now, as an adult, she understands the sorghum she grows in eastern El Salvador is so much more versatile.

“We have learned how to make sorghum pizza and sorghum biscuits,” says Sánchez, of a WFP cooking and nutrition workshop for smallholder farmers she attended. “The sorghum pizza is very good - the children love it.”

The workshop is part of a broader WFP push in El Salvador to promote the production, processing and consumption of sorghum - a gluten-free, drought-resistant cereal high in fiber, vitamins, minerals and antioxidants. Together, these attributes pack a powerful punch in building resilience and healthy diets in El Salvador, where more frequent and intense climate shocks count among top development challenges.

“Smallholder farmers have learned to produce sorghum more efficiently for multiple uses, including gluten-free bakery products and Biofortik, a fortified drink for schoolchildren,” says WFP El Salvador Representative and Country Director Riaz Lodhi.

The WFP project teaches farmers like Sánchez to cultivate sorghum using climate-friendly techniques, and about the crop’s nutritional benefits. It links them to local bakeries, whose sorghum products offer a nutrient-rich, gluten-free alternative for consumers.

“I didn't know that sorghum had essential nutrients for humans,” says José Antonio Cárcamo, another smallholder famer in the project. “I liked it and learned a lot about it.”

For farmer Sánchez, the WFP project offers another plus. “We women learnt strength and courage through empowerment training, ” she says of fellow female farmers. “We are showing how we can also earn a living - and teach our children how it is done.”

WFP’s superfoods projects in Bolivia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Kenya, India and Uganda are funded by donors including China, Germany, Ireland, Novo Nordisk Foundation for Uganda, and WFP USA.