Spiking hunger and prices: Sudan’s neighbours grapple with a refugee crisis

Update June 27: Read new IPC report on Sudan here

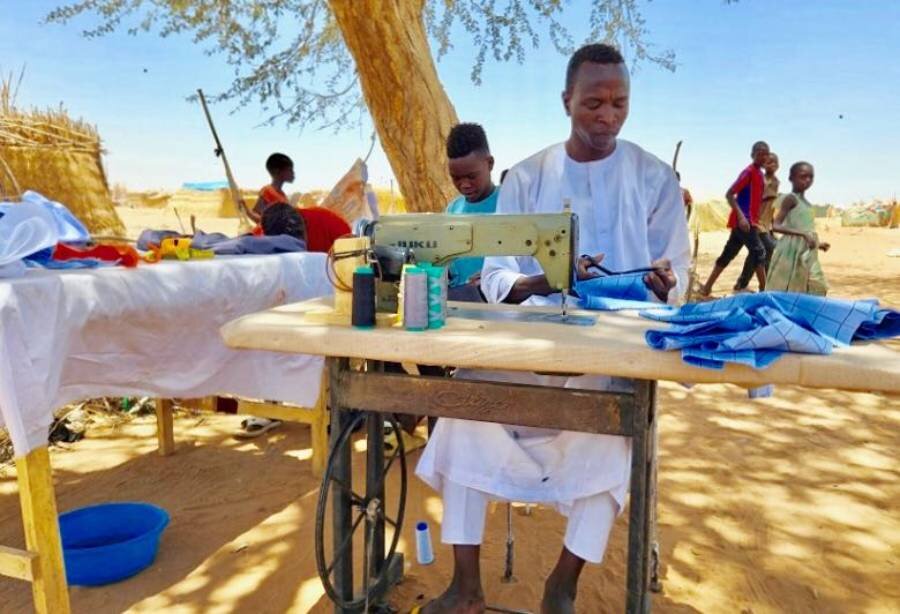

At a tent settlement in the Chadian border town of Adre, Ahmat feeds blue cloth into his foot-powered sewing machine, as a popular folksong from his native Sudan plays in loops over a loudspeaker. The small tree overhead barely dents the searing sun.

“Sewing is all I can do here at the camp,” says the 35-year-old tailor, whose last name is being withheld for his security, as he nods his head to the music’s vibes. “People come with their cloths, and I make for them Sudanese-styled dresses, shirts or pants.”

Sudan updates: WFP scaling up as hunger catastrophe looms

This is the second time in two decades that Ahmat has sought refuge in Chad from conflict roiling his homeland. Even as he calls for peace to return to Sudan, he is not sure that will happen anytime soon.

“I need to be in a stable country, where my children can go to school,” Ahmat says.

As Sudan’s crisis drags on, the fallout is growing in neighboring countries. Of the more than two million war-displaced people now living outside Sudan’s borders, more than half are in Chad and South Sudan, countries already grappling with soaring hunger of their own.

Now, with the rainy or lean season setting in across the region and stretching through August – turning roads into muddy tracks, and complicating humanitarian deliveries – food insecurity risks climbing higher.

The World Food Programme (WFP) is responding to the growing food insecurity but the challenges are immense. In Chad, for example, we aim to reach more than 2 million people, including refugees, with emergency lean season assistance. But with funding tight, especially in South Sudan, we can only support the hungriest.

“Providing adequate and timely assistance at scale is essential to maintain stability and minimize tensions among crisis-affected communities over limited resources in Chad,” says WFP Chad Country Director Enrico Pausilli. “With the compounding effects of climate shocks, security and economic crisis, large-scale investments in resilience are also needed to reduce the increasing humanitarian needs over time.”

Feeding a bigger crisis

In South Sudan, the nearly 700,000 war-displaced arrivals from Sudan count among some 7 million people already facing acute or worse food insecurity. Thousands of the newcomers – like Zahara, whose family fled their home in Sudan’s East Darfur state – are still crossing the border every week, hungry and traumatized.

“After the third aerial bombardment, we made the decision to leave,” says the mother of four, cradling her 14-month-old daughter Moona in her arms. “It took us two days to reach the border. We carried water in a container and biscuits for the children, but they were really hungry when we finally arrived.”

The toddler struggled through the journey. At Wedweil refugee settlement, in northwestern South Sudan, Zahara took her daughter to a health center, where she was diagnosed with malnutrition.

Today, Moona is gaining weight and playing again, thanks to WFP nutritional supplements. But in the crowded refugee camp, with heavy rains expected, there is the threat of waterborne disease.

That is not the only worry. Sudan’s war has disrupted South Sudan’s all-important oil exports, pushing the economy into freefall. The South Sudanese pound has plummeted by 60 percent, while food and fuel prices have skyrocketed. WFP projections indicate the country’s economic crisis will likely push an estimated half a million more people from moderate to severe hunger as staple items become unaffordable.

“Before this economic crisis, my children used to eat twice a day – but now there is no way,” says Juba native Mary Yike, as she shopped for basics at a market in the capital. “The children wake up in the morning and don’t eat anything until night. This situation is getting worse. When you have six children, it is difficult to feed them.”

Since Sudan’s conflict erupted in April 2023, WFP in South Sudan has reached nearly 557,000 of the war displaced crossing the border, and continues to assist new arrivals. But today a perfect storm of events risks driving food insecurity to the extreme.

“South Sudan is an already protracted humanitarian crisis which is deteriorating rapidly,” says Mary-Ellen McGroarty, WFP Country Director in South Sudan. “Our fear is that hunger and malnutrition will reach never-before-seen levels with the continued devastating consequences of the war in Sudan, and imminent flooding in areas already suffering acute levels of food insecurity.”

She adds: “We need a ceasefire in Sudan and strengthened social safety nets in South Sudan to help stem the wave of severe hunger and malnutrition.”

Spiking refugee numbers

Chad, too, is grappling with alarming food insecurity that will only get worse as the lean season bites. An estimated 3.4 million Chadians and refugees are projected to face severe food insecurity during this period, a hunger uptick worsened by climate shocks, high food and fuel costs – and the refugee crisis.

Over the past 14 months, roughly 600,000 Sudanese refugees have arrived in the arid Sahel country – doubling the number of asylum seekers in Chad, which already hosts one of Africa’s largest refugee populations. Most are sheltered in 39 spontaneous sites in eastern Chad. Like tailor Ahmat, many carry the burdens of hunger and trauma.

“Sudan has been in war for so long. But the one that started in 2023 was particularly violent,” says Ahmat, who hails from Sudan’s West Darfur capital of El Geneina. He also sought shelter in Chad as a teenager two decades ago, when the first Darfur conflict broke out.

But he later returned to his homeland, becoming a prominent dressmaker in El Geneina. He owned several electric sewing machines, a family car and two motorbikes. All were stolen by attackers, who burnt his workshop and house to the ground.

“Most of the people were attacked in their homes, their belongings were stolen,” Ahmat says of fellow El Geneina residents. “Many were killed on their way to Chad. The road was covered with dead bodies.”

In Chad, he and other refugees rely entirely on humanitarian assistance. Many, along with members of host communities, show poor or borderline food consumption levels, according to WFP and other assessments. Nearly half of all children suffer from anemia.

“Life is not easy here,” Ahmat says.

He is worried about the future of his children – and those playing around his open-air workshop.

“We are waiting for Allah to help us,” Ahmat says. “One day our life will be better.”

WFP’s response in Chad and South Sudan is made possible thanks to generous contributions from Canada, the European Union, Germany, Japan, Sweden, Switzerland, UKAid, United Arab Emirates, UN CERF and the United States of America.

WFP's response to the Sudan crisis in South Sudan is made possible thanks to generous contributions from Canada, the European Commission (ECHO), France, Germany (GFO), Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Private donors, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, UN CERF, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom and the United States of America