School meals coverage is surging, but it's not enough

After coronavirus lockdowns and the economic blowback from the war in Ukraine, school meals have rebounded sharply and are today reaching a record number of young students worldwide.

Yet even as many governments strengthen their commitments to school meals, some of the poorest are struggling to finance them. Donor funding is patchy and realizing a 2030 goal – that every young student gets at least one nutritious meal during schooldays – remains daunting.

This mixed report card backdrops the first international meeting of the School Meals Coalition in Paris Wednesday (18 October). Hosted by France, the two-day summit gathers representatives from 55 countries, including heads of state and local governments, lawmakers and key Coalition drivers, including the World Food Programme (WFP).

“The conversation in Paris is going to be about we move the agenda forward – how to scale up programmes to reach all the children in the world,” says Carmen Burbano, Director of WFP’s School Feeding Unit.

For the poorest countries, however, struggling to meet massive development demands with shoe-string budgets: “We still don’t have the financing solution that meets the challenge,” Burbano says.

These and other issues will be up for discussion this week through the Coalition – a two-year-old network that has grown to more than 90 member states and 100-plus partner organizations.

Among other key goals, Burbano says, WFP hopes the Paris meeting will motivate governments and donors to invest more in school meals, help bring school-meals goals into major forums like the Group of Seven (G7) and Group of 20 (G20), and allow new voices – from mayors to academics – to help shape the discussions.

Also essential: mobilizing new financing, including from multilateral financial institutions.

Ahead of the summit, however, Burbano points to one key achievement: “We’ve managed to position the well-being of children in the (global) conversation,” Burbano says. “Getting so many governments to agree on something is not very common these days, in a very fragmented multilateral world.”

Breaking the hunger cycle

Today, authorities are earmarking billions more dollars for school meals than just a few years ago; low-income countries alone have seen a 15 percent spending boost.

Roughly 418 million schoolchildren worldwide now benefit from school meals – 30 million more than during pre-COVID-19 days. But millions more are still denied access – demanding major efforts to realize the Coalition’s 2030 goal of feeding all 724 million students who need them.

“If I were the Prime Minister, I would give children food three times a day: before they start their classes, at break time, and after school before they go home,” says Solomon, a young learner in Haiti. “Because when they get home, they may not find any food and spend the whole day hungry.”

Students like Solomon count among 20 million children eating WFP school meals in 74 countries – in programmes in which governments are the main drivers. The paybacks are multiple; school meals support agriculture, health, nutrition and education among other sectors, with every dollar invested delivering US$9 in returns.

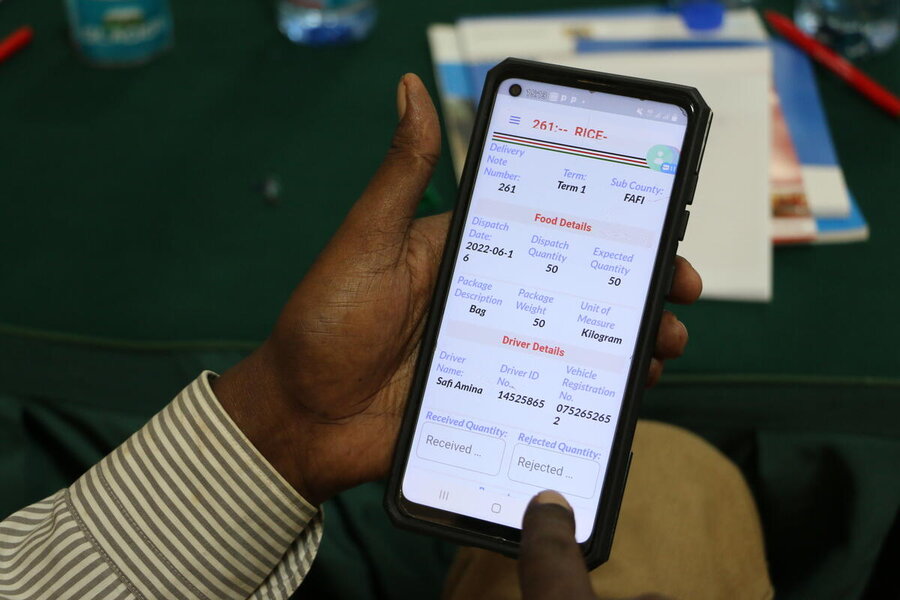

In Kenya – where WFP works with the Ministry of Education to provide school meals to 1.6 million children – the Government plans to more than double the school meals budget to US$35 million in 2024, compared to US$15 million this year, and has set ambitious targets to boost coverage from the current 1.6 million children to 10 million by 2030.

“It’s increasing the percentage of local food purchases so that smallholder farmers are connected,” Burbano adds, regarding Kenya’s school meals strategy which reflects WFP’s own community-based, locally supplied Home Grown School Meals initiative. “It’s increasing the diversity of food children eat, so it’s not just rice and beans.”

In Honduras, where WFP supports the Government in delivering food to more than 1 million schoolchildren, authorities are moving to supply clean energy to every participating school.

WFP is also working with cities like Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, which provides its own, universal school meals coverage to young students. Mayor Adanech Abebe will be attending the Paris summit.

“The school meals programme is run by the city,” Burbano says, “but we provide technical assistance and backstopping.”

New commitments

She expects the Paris conference to see a raft of new country commitments to school feeding – likely sparking a snowball effect with buy-ins from donors and other Coalition members. But gaping holes remain.

“The biggest challenge is in low-income countries, and how they can afford these programmes,” Burbano says of countries WFP works with especially closely.

“These are the governments that are slashing budgets everywhere,” she adds of especially fragile states, “the ones that are going to feel the effects of climate change and disasters more often.”

It will also take major and longstanding funding commitments to reach universal school meals coverage in just seven years.

Investment options on the table, Burbano says, include debt swaps – in which indebted countries invest in a mutually agreed development project instead of paying back their creditors. WFP has already negotiated ten such agreements to date for school meals and other key programmes, amounting to more than US$145 million.

Bringing in new, multi-year financing, including from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, is another priority.

“That’s the biggest conversation,” Burbano says. “How to nurture the momentum for school meals programmes and bring other voices to the table, so it continues to grow.”