School feeding in Sudan: Before the coronavirus and beyond

By Gabriel Valdes

Hamza, a World Food Programme (WFP) driver, commands our four-by-four on what is an uncompromisingly treacherous road — in some spots, the sand is half a metre deep and we keep skidding off the road and getting stuck.

WFP and UNICEF warn future of 370 million children in jeopardy as school closures deprive them of school meals

We arrive in Megiseiba, a village in Bara, in El Obeid, in North Kordofan, Sudan, and head to its only school. It's January, and well before schools are suspended, in the country of nearly 42 million, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

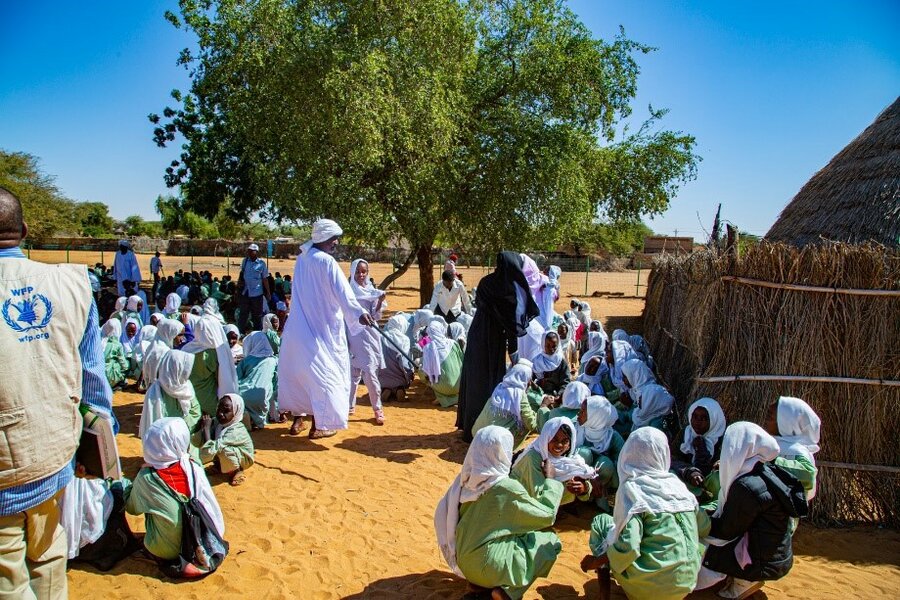

The whole community along with representatives from WFP's cooperating partner and State Ministries are waiting for us. Children greet us with a nice performance. Schoolgirls sing a song — a plea not to be married off and to be given, instead, the opportunity to remain in school and go to university. Mothers begin dancing around the girls, and then the boys and elders quickly join in.

‘Boys will join their fathers in farms while girls are often married and taken away from school'

The school has 260 students, a number considerably higher than when the WFP project began. In many villages of Sudan, opportunities are slim for children who reach the sixth, seventh, or eighth grade: "Boys will join their fathers in farms while girls are often married and taken away from school," says WFP staffer Mohamed Eltigani.

School meals in Sudan are a strong incentive for parents to send their children to school. However, schools are closed until September, as one of the measures to halt the spread of COVID-19. To addresses schoolchildren's food and nutritional requirements during the COVID-19 crisis, WFP is currently providing take-home rations in lieu of the in-school meals in 11 states, targeting nearly 1.1 million students enrolled in WFP-supported schools, including for the first time 180,000 primary school children in Khartoum State.

WFP is also planning to reach an additional 512,000 primary school children starting September in four new states, aiming to bring the total of children in its programme to over 1.6 million by the end of the year.

As the COVID-19 crisis pushes up levels of hunger among the global poor, the World Food Programme and UNICEF are urging national governments to prevent devastating nutrition and health consequences for the 370 million children missing out on school meals amid school closures.

This June, UNESCO, UNICEF, WFP and the World Bank issued new guidelines on the safe reopening of schools amid ongoing closures affecting nearly 1.3 billion students worldwide.

‘The locusts are a moving target and we are racing against time'

"Rising inequality, poor health outcomes, violence, child labour and child marriage are just some of the long-term threats for children who miss out on school," Henrietta Fore, UNICEF's Executive Director, has said. "We know the longer children stay out of school, the less likely they are to ever return. Unless we prioritize the reopening of schools — when it is safe to do so — we will likely see a devastating reversal in education gains."

Nutritious food needs to be available and accessible at all times without interruption. As Asif Niazi, Head of Programme in WFP's El Obeid Area Office emphasizes: "Achieving these goals in a sustainable manner requires a lifecycle approach, a combination of complementary activities across nutrition and livelihood."

In Bara, WFP engages the community with the school meals and the Productive Safety Net (PSN) programmes. The PSN farm complements the positive consequences of school meals and also acts as an income-generator for mothers who are empowered through capacity-building initiatives and become economically independent with the sale of their products in the market.

By involving families in a wide array of activities, WFP ensures resilient and self-sustainable ecosystems within communities and families that also result in higher retention rates in schools.

WFP staffer Salwa Jallab says: "Empowered mothers and economically stable families no longer require their daughters and sons to drop out of school. Fewer drop-outs means more children in school, brighter futures, improved livelihoods."

As these children grow older, they will spread their knowledge and increase the resilience of remote villages such as Megiseiba. Implementing activities in a cohesive and coordinated manner creates a dynamic change among communities, as well as opportunities for change and for long-term sustainability and resilience. By combining its activities in El Obeid communities, WFP in Sudan is addressing all four pillars of food security to reach zero hunger: availability, access, utilization and stability.