People with disabilities: Venezuela’s WFP school meals help ensure it’s never too late to learn

It’s 5 a.m. in Araya, a small town on the northeastern coast of Venezuela. The houses are quiet and dark, except for one.

Luis García has risen early, as usual. It will take him an hour to prepare breakfast and get the bathroom ready for his son, Luis Enrique. By the time the father manages to have Luis Enrique impeccable and ready to head out the front door, it will be almost 8.

It could be the beginning of a normal day for any family, anywhere.

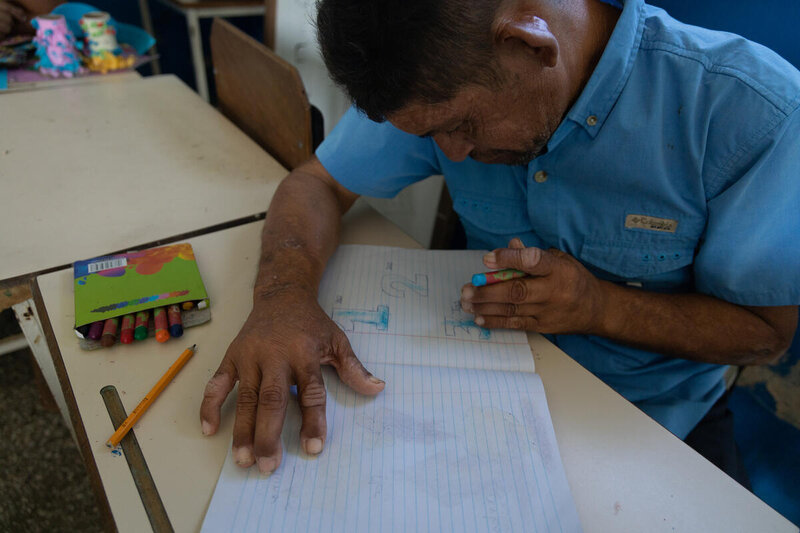

But Luis García is 72; and the son he taks care of is a 52-year-old man with a cognitive disability — who is beginning this morning his very first day at school.

Beyond an education, Luis Enrique is also certain to receive a World Food Programme (WFP) school meal.

For over half-a-century, Luis has kept his son at home, “well protected, where no one would hurt him.” he says. What changed his mind? Why now?

“I was convinced that I could give him everything he needed at home. But not anymore,” he says. “Especially the food.”

When times were better, Luis would have weekly plans for the meals. “Now,” he says, “we eat what I can get day by day.”

Hard choices

In Venezuela, eight out of ten families sacrifice their most valuable possessions or their entire income to secure just one meal per day. Some stop sending their children to school because they have nothing to give them for breakfast. This is often the case for families in which a member has a disability, which can increase household expenses.

These families love their children and do everything to ensure that they have opportunities. Often, they make tough choices: medicine or food. Education or food.

In Araya, a nearly 10-hour drive east from the capital, Caracas, people once depended on salt production for a living. But this industry has been paralyzed for years. Working-aged men and women have migrated to nearby cities in search of jobs, or emigrated to other countries, often leaving elderly people in charge of their children and homes.

But for some, those hard decisions have eased since 2022, when WFP introduced a school meals programme in Venezuela that benefits children, adolescents and adults with disabilities. When the programme started, however, many of those people — including Luis Enrique — were not even enrolled in schools.

Today, more than 15,000 children, adolescents and adults with disabilities and their families receive WFP meals in 300 schools across eight states. This number continues to rise as the programme expands to new municipalities with higher rates of food insecurity.

Early evidence shows that school enrollment of people with disabilities has jumped 30 percent in establishments with WFP meals — which deliver paybacks in both education and food.

Venezuela’s public schools also offer safe spaces that provide education and life skills, protection, health care and other essential services to children, adolescents and adults with disabilities, based on their condition and age, observers say.

Although the infrastructure and resources are minimal in most schools, and many educated professionals have had to leave the country, staff and families are creative and committed. They believe schools can create opportunities for their children, so they do everything to keep them running.

Through the schools, WFP can also reach out with food and other assistance to families of people with disabilities, which are often headed by single women or the elderly. This support provides some relief for the family budget and allows overworked caregivers to care for themselves as well.

Food conquers fear

As the school meals coverage continues to expand, WFP aims to better understand the needs and capabilities of people with disabilities, and any barriers they might experience.

We and our partners also want to reinforce their access to essential public services like healthcare and other support, and facilitate connections among their caregivers.

For father Luis García, the school meals offered an incentive to break with 52 years of fear. His son has not missed a single school day since.

“I am beyond happy to see my son's progress and how much he loves going to school,” García says.

"Some people say it's too late, but I don't think so,” he adds. “Now I know he can do well when I am no longer around.”