Mother’s Day interview: The cautious optimism of Princess Sarah Zeid

By Ljubica Vujadinovic

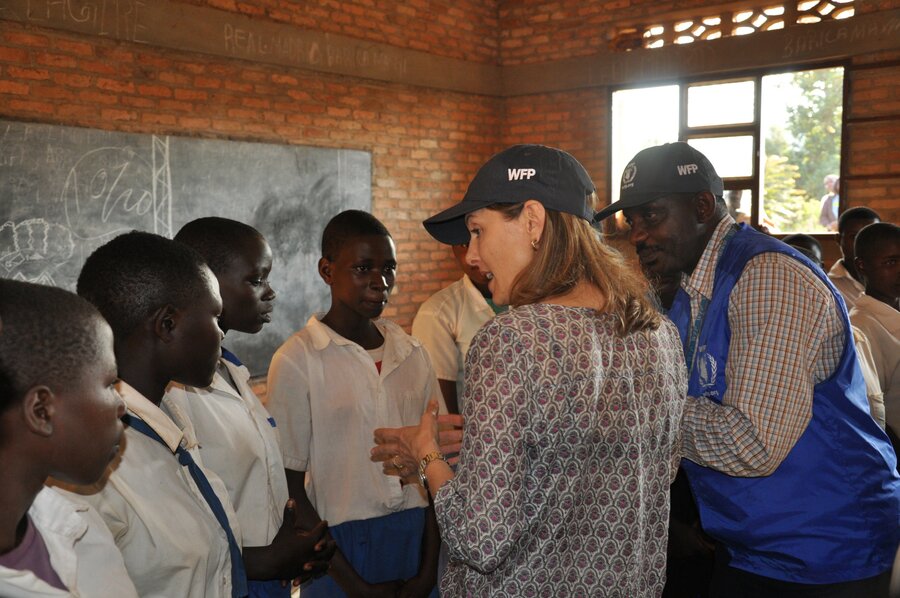

As a World Food Programme (WFP) special adviser on maternal and newborn health and nutrition, Princess Sarah Zeid of Jordan is ever keen to champion health, wellbeing, empowerment and the contributions of girls and women in fragile settings that make them vulnerable to food insecurity.

To mark Mother's Day, she shares her personal experiences, both as a mother of three children and an advocate for mothers in countries affected by violence and conflict.

‘Critically ill, I was determined not to die and leave my children and new baby girl without a mother.'

Princess Sarah became a Special Adviser to WFP in 2018 — the organization is currently ramping up efforts to assist 100 million people in more than 80 countries, in a bid to avert a "hunger pandemic" triggered by COVID-19.

The focus of her work with WFP — which has taken her to Pakistan, Bangladesh and countries in Africa — is mortality among mothers and children; and morbidity, the mortality of children aged under 5.

You've worked in the humanitarian field for more than two decades, from being a UN staff member in your early career to becoming an advocate for maternal and newborn health. What inspired you to become a voice for maternal and newborn health?

Ten years ago, moments after my third child was delivered, I suffered from an amniotic fluid embolism, a rare and catastrophic event. For the next 24 hours my doctors did not know if I would live. Although critically ill in the ICU, I was wide awake, having to confront the possibility of leaving my then eight-year-old son, six-year-old daughter and newborn baby girl without a mother.

I am physically and mentally healthy today because I had access to quality health services. And my baby, when I was unable to care for her, was kept safe and healthy. Every mother should have access to quality services, before, during and after their pregnancy.

I know there are numerous medical reasons why my daughter and I survived and we were lucky to have access to excellent care — we were in Washington, DC. But, secretly, I like to think some of it was down to my own bloody-minded determination. I was not going to die and leave my children and new baby girl without a mother.

Now, I try to put that same level of fierce determination into my work supporting organizations like WFP, working on the front lines of response and prevention, prioritizing the most vulnerable women, newborns and children. The majority of maternal and newborn deaths and delivery-related injuries, the terrible loss, trauma, and pain are entirely preventable.

If we — governments, donors, agencies, programmes and NGOs — prioritize and invest in the comprehensive health and nutrition needs of women and girls, then we will see real change, sustained progress and a massive reduction in the loss of life.

This requires investing in women and girls' education, ensuring access to lifesaving, life-changing information, and ensuring their right to make informed decisions.

You've met many women and mothers in some of the world's most vulnerable communities, where every new day is a new struggle for survival. What are your strongest impressions from these missions?

Sitting with groups of women and children, speaking with them and sharing experiences, the strength of mothers always astounds me. And it's not just mothers, it's women who care for children, grandmothers and ‘aunties'. Women around the world — mothers around the world — all want the same thing for their children: that they be healthy, educated, safe and have prospects.

Too many women, however, are locked in an unforgiving daily battle for mere survival. Earlier this year, I was in Chad to better understand the complexity of issues overwhelming the Sahel. Mao is a city in the northwest of that enormous landlocked country, where for miles around there was nothing to see but sand and dust. Sun, wind, sand and flies — it felt as though there was no escape from any of it, especially for the children who were too weak and no longer feeling the flies crawling around their eyes, noses and mouths.

When you sit with women, after a while, you can almost feel the truth of their hardship and suffering. It comes in a whisper or defiant cry that causes a ripple through the group who glance nervously around for someone to tell that person to stop talking.

In Mao, their truth was 12-year-old girls dropping out of school to get married — no sanitation facilities or educational supplies in a school with one teacher for more than 80 children.

In other groups of women and other conversations, it is the endless hours consumed every day fetching water, firewood or working on land they do not own; babies born away from health facilities because there were no funds for the horse and cart; wounds that won't heal for malnourished children too small for their age; women and children abandoned by men; the aches, pains and exhaustion from having so many children; the one meagre meal a day; domestic abuse; stillborn babies and a future with no hope.

I was sitting in the desert with a grandmother, who had her grandson between her legs, and I was asking her how many pregnancies she'd had. And she told me she had six children and 10 pregnancies, then she started to weep. It is the pain a woman never forgets; that pain never goes away. There are of course wonderful moments and encounters full of laughter, but my purpose is to make visible the invisible and to try to give their needs and suffering a voice.

You advocate for more focus on the first 1,000 days — from pregnancy to a child's second birthday — as a strategy to reduce malnutrition and ensure social and economic development.

Nutrition is the keystone and it plays a foundational role in a child's development and their country's ability to prosper. Poor nutrition in the first 1,000 days causes irreversible damage to a child's growing brain, affecting their ability to do well in school and earn a good living.

Evidence shows that countries which fail to invest in the well-being of women and children in the first 1,000 days lose billions of dollars to lower economic productivity and higher health costs. Worse still is that a person's physical health, cognitive capacity, future and potential is diminished before it even really begins.

One of the most exciting initiatives we've been working on is a partnership between the WFP and the Islamic Development Bank, with nutrition during the first 1,000 days in OIC (Organization of Islamic Development) member states at the forefront. Muslim-majority countries have some of the worst statistics and indicators — we have the highest levels of maternal and under-5 mortality, for example.

Combining the strengths of these two extraordinary organizations and applying the very best of what each one does, is an innovation in the fight against malnutrition.

We can do so much more and better for the most vulnerable — who are also at the heart of a country's future — during this most critical time. Iraq, Syria, Mali, Yemen — countries that have seen conflict, contagion, and the impact of the climate crisis for many, many years… how many ‘first 1,000 days' have we lost? How much potential productivity, how many years of education, GDP growth, culture, art and good health have been lost because nutritional needs have not been met during the first 1,000 days?

In 2020, what do you feel most optimistic about in terms of maternal and newborn health? And what areas do you feel need more attention, or even a complete ‘turning of the tide'?

Sitting in New York City watching the rapid-fire spread of COVID-19, it is quite hard to feel optimistic about anything. The ‘silver lining' will be if governments, the private sector, multi-lateral organizations and so on, emerge from this experience with a new political, financial and deeply human understanding of why there must be sustained investment and commitment to the Global Goals.

The pandemic is revealing both systemic weaknesses in every country which can no longer be ignored, and the strength which comes from greater cooperation. Here in New York, parents and students are fretting about missed weeks of schooling, loss of income and livelihood opportunities. We have been told not to visit doctors' offices or go to the hospital, to keep our hands clean and practice social distancing.

I hope when this is over, we do not return to business as usual, relieved our lives can continue, and turn our back on the rest of the world. Is it too much to hope that this experience will move us to act when we read about children denied even the promise of an education, communities without clean water, and families without access to medical assistance?

What gives you hope?

The WFP staff and partners I spend time with in the field fill me with hope, especially the young colleagues, who are committed, courageous and passionate about the people they serve. And babies, because they bring me joy!

Princess Sarah is a former United Nations staff member. She worked in the Department of Peacekeeping Operations and was the Desk Officer for Iraq in UNICEF's Office of Emergency Programmes. She holds a BA in International Relations from the University of St Thomas in Houston, Texas, and an MSc in Development Studies from the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.