Lake Chad: Cursed by conflict and climate change

In the Lake Chad region, climate change and conflict exacerbate each other. On one hand, indiscriminate and continuous violence prevents people from adapting to new climate conditions. On the other, extreme poverty and hunger, triggered by harsh weather, push many to join the armed groups.

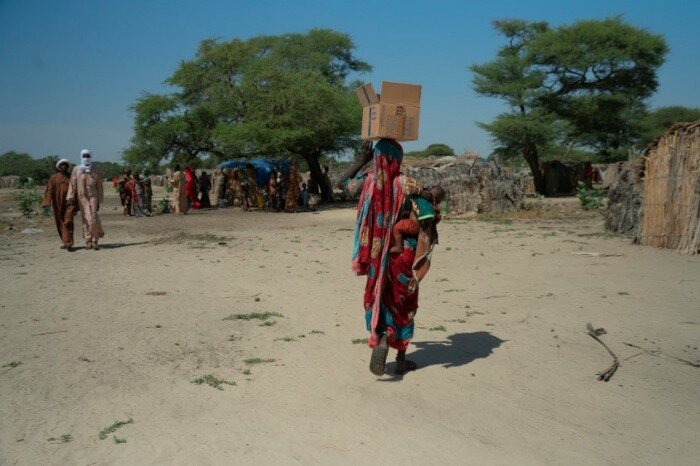

Hawa Kali was displaced twice in only seven months. Conflict and climate change are making it hard for people in Lake Chad to find a safe place where food is not a constant worry. Photo: WFPWFP/María Gallar

Hawa Kali and her extended family fled their village in fear for their lives following the deadliest jihadist attack on Chadian soil that killed 100 soldiers in March 2020.

“We left our village because we were scared that Boko Haram would raid it and kill us. We are almost forty people; grandparents, children and in-laws. We walked for ten days until we reached Kaya,” she explains. “Last week, we were forced to leave Kaya too, because we had nothing to eat. We lost our harvest due to floods.”

In only seven months, Hawa was displaced twice. First by conflict and later by a climate-related disaster. She tells her story as we sit in the shrinking shade of a makeshift hut. There are abandoned settlements scattered all over the region; skeletons of huts made of straw and mud like Hawa’s and the remains of torn tarpaulins and blue plastic bags tangled in bushes.

Toukoul Abakar fled her home to Mar four years ago. Displaced families have no land to grow their food and depend on WFP food assistance for survival. Photo: WFPWFP/María Gallar

When Toukoul Abakar escaped a Boko Haram attack four years ago, she did not have time to pack her belongings. “I will never forget that villagers gave me pots and a mat, and helped me build a house when I arrived here. When new people come to Mar, the neighbours share the little they have,” she says. “The problem is that there is no land. Displaced families, like mine, are not able to grow food.”

The number of internally displaced people on the Chadian side of the lake has doubled over the past twelve months from 169,000 to 336,000 people according to the International Organization for Migrations (IOM). Shaken and stirred, environmental degradation and terrorism continue to exacerbate hunger and malnutrition. Internally displaced people, refugees and host communities depend on the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP)’s food baskets to survive.

Mariam (right), carrying her baby girl at the nutritional centre. In the Lake Chad region, malnutrition is always on the rise before the harvest. Mothers like her collect nutritional supplements to treat their children. Photo: WFP/María Gallar

Mariam has always lived in Bol, the main town on the Chadian side of the lake. “It is hard to feed my children several times a day, but I do everything I can so they eat at least one meal that is nutritious and vitamin-rich,” she says. She and her husband do not have a job and their seven-month-old baby girl suffers from malnutrition. “Before Boko Haram, it was already hard to make a living around here, but today there are many more people.”

At the health centre, dozens of women wait under the trees, sitting cross-legged with their babies on their knees. Mariam is one of them. During this time of the year, before the harvest, malnutrition is on the rise and many mothers come to collect nutritional supplements. With more people and fewer resources, solidarity networks are on the brink of collapse.

Climate change and extremism are making 14-year-old Abdoulaye eager to leave Lake Chad. Photo: WFP/Clotilde Bertet

Moreover, climate nowadays is indecipherable to the inhabitants of Lake Chad: it rains when it should not, temperatures soar burning your nostrils and the level of the lake is constantly changing, covering and uncovering different islands every day, flooding croplands and drying pools that become barren and unproductive due to natron, a mineral akin to salt.

“We can no longer walk to the places where we used to farm. Boko Haram has taken control over our land,” says 14-year-old Abdoulaye. “Boko Haram can walk on water!” It’s his way of explaining that the jihadist group know the area like the back of their hands and that its members could be hiding anywhere. “Although we work hard, life is hard. I would like to leave. Who knows what I will find!”

People like Hawa Kali, Toukoul Abakar, Mariam and young Abdoulaye no longer know when and where to plant, they ask themselves whether they should risk their lives to go fishing in the islands — where Boko Haram could be hiding — or if they should flee the lake once and for all.

Learn more about WFP’s work in Chad