Kenya: Cash grants provide critical relief for families in the grip of hunger

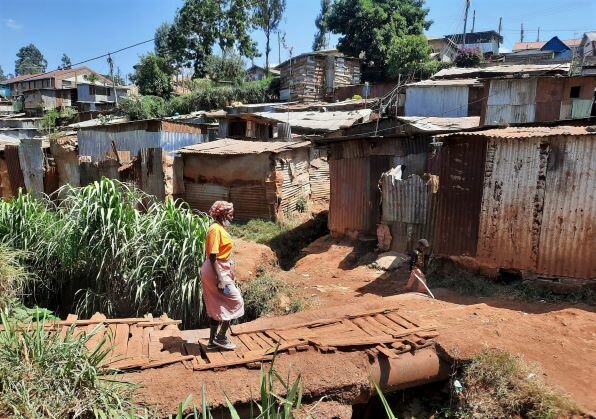

Narrow alleys twist and turn down the slope snaking between the closely packed tin shacks. This maze of paths contains the hundreds of homes that make up Moroto Simitini.

The village is in Kenya’s coastal city of Mombasa, where the World Food Programme (WFP) is providing emergency cash to families who have lost incomes due to COVID-19. Each receives 4,000 Kenya shillings (US$37) per month, for three months.

Here, the closer you are to the seafront the poorer you are. You sit at the bottom of the drain chain. Waste washes past your doorstep — or through it if it’s not flood-proofed.

This village is home to nearly 30,000 people — almost all work menial jobs. Women wash and clean homes in neighbouring estates to feed their children and the men transport goods on pushcarts or on their backs in return for money.

Benedetta is a mother of five who earns a living doing the washing for well-off neighbours. Since the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic she has struggled to find work, with guards at gated residential compounds no longer letting anyone in from the villages.

Now, with vaccines available, health workers, teachers and security personnel are first in line for the jab, followed by older people and those with underlying conditions — 35-year-old Benedetta and her peers, however, will have to wait longer.

Her neighbour, Dorcas Adaye, recalls life after lockdown was introduced: “Most days, I failed to find any work and I would return and sit at the edge of the village, waiting and hoping to find someone to lend me some cash to buy some flour.

“I would stay there until dusk because I didn’t want to return home empty-handed and have to explain myself to my hungry children.”

Chirindo Mwambui lives with her four children a few blocks down the slope.

She worked at a café making lunch for high-school children. When schools were forced to close, so did the café. Chirindo lost her job.

“I search for work every day and when I’m unlucky, I borrow money to feed my children,” she says. “If I can’t get cash or food on credit, we have no choice but to drink strong tea and sleep.”

There are yawning holes in the walls of her home and the roof is only partially finished. The room measures about 4 by 3 metres. There is only one bed which occupies most of the room — the rest is the kitchen and storage. It is difficult to manoeuvre in this space, yet five people live here: Chirindo, her 22-year old son, teenage daughters and youngest son.

“I bought food and paid off my debts with the cash I received,” she says. “I also paid school fees and bought poles and iron sheets with which to construct this house. Although the money ran out, it is better than my previous shelter which was made from cardboard and mosquito nets. But if it rains, everything in here will still get soaked.”

“I would like to open a food kiosk, it is the safest business because people must eat,” she says. “I won’t fail to make money and I will be able to take care of my children." Then, she asks: “Can you help us start small businesses so that we can earn through our own sweat?”

Hard times

In partnership with county and national governments, WFP has provided 23,000 families in Mombasa’s informal urban settlements with half their monthly food needs for three months.

Their needs, however, are bigger than just food, and the economic hardship continues.

Leah Wairimu runs a food kiosk in Kibagare, a village adjacent to the upmarket Loresho estate, in Kenya’s capital city of Nairobi. Leah’s family is one of 68,000 in Nairobi who have received cash assistance from WFP — each getting 4,000 Kenyan shillings (US$ 37) a month for 12 weeks.

On a busy day, she'd serve ten plates of food which sell at 50 shillings each (less than half a dollar). But at the start of the pandemic, all eateries closed. A widow raising five sons, her only source of income disappeared overnight.

“I spent the first two rounds of cash [from WFP] purely on food,” she says, “Then, I bought some vegetables and fruits and stocked up a small grocery stall.”

“I was not allowed to cook and serve clients ready food, but I could still sell kale, tomatoes, dania [coriander], and make a small profit.”

By her fourth and last cash transfer, her grocery business was already picking up. The business is now running and giving her an extra stream of income.

Down the road from Leah’s kiosk, Mary is a beautician offering women’s hair extensions, manicures, pedicures or facial makeovers. Mary is the sole provider for a family of nine: her husband, their three children and four orphans left behind by her brother. Within a month of COVID-19 being detected in Kenya, Mary’s business plummeted and she was forced to shut down her shop.

“I was drowning in bills. With the four cash transfers, I bought my family food and set some aside to revive the hair salon,” she says. “Business is still slow but things are looking up. I now serve two or three clients a week.”

Mary is keen to grow her hair salon business and knows exactly what she needs to make it happen.

“What we really need are grants to allow us to grow our different business ventures,” she says. “That will leave a permanent change.”

Supporting those in need — together

Many, especially the young, are calling for work and business opportunities.

“When we began the cash transfers in Nairobi, we thought it would be a sprint,” says Michael DeSisti, regional director at USAID's Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance, East and Central Africa, a key partner of WFP.

“But we soon realized that we were in for a marathon. Kenya requires longer-term support to build on the gains made so far. We cannot afford to lose the momentum now.”

As the programme ends, WFP will have provided life-saving cash to almost 95,000 families or about 378,000 individuals in Nairobi and Mombasa.

“We couldn’t have achieved this without support from partners such as USAID, our biggest donor, and the national and county governments both in Nairobi and Mombasa,” says Lauren Landis, WFP’s Country Director in Kenya. “However, our helpline has not stopped ringing. People are desperate to be included in the cash transfers — but we are unable to take on more.”

WFP is also treating malnutrition in children aged under 5, pregnant and breastfeeding mothers, and older people, through health centres in the informal settlements of Nairobi and Mombasa.

“We are in a strong position to provide livelihoods support and widen social safety nets to better protect these deeply vulnerable families, and we are knocking on the doors of our donors to help us realize this,” adds Landis.

WFP’s provision of cash transfers in Kenya’s informal urban settlements are supported by USAID, Finland, Poland and Sweden.