How school meals are empowering girls in South Sudan

Girls in South Sudan are more likely than boys to be excluded from education. In some parts of the country, it is estimated that over 75 percent of primary-school-aged girls are not in school.

Conflict, poverty, early marriage, teenage pregnancy, and cultural and religious views are among factors driving educational inequality that hinders the prospects of girls.

In fact, UNICEF estimates that a girl in South Sudan is more likely to die during childbirth than complete secondary school education.

The World Food Programme’s (WFP) school feeding programme provides daily hot meals to 500,000 children in 1,100 schools across South Sudan, an essential safeguard contributing to increased enrolment and encouraging parents to keep children in school.

Critically, school feeding helps put a stop to early marriage which can trap young mothers in particular in poverty, posing huge risks to their health.

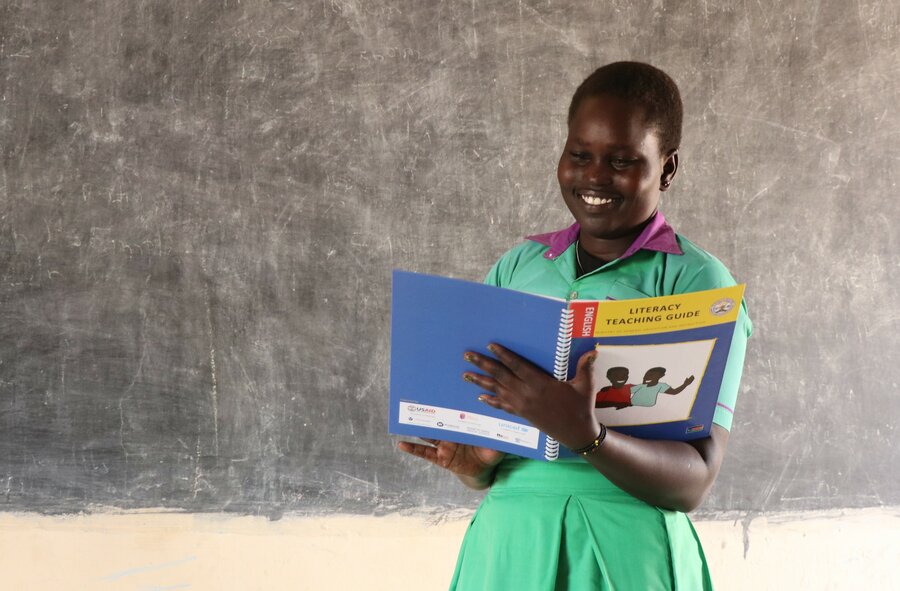

Despite the challenges faced by girls in South Sudan, some are determined to stay in education, obtain professional qualifications and reverse the grim statistics — girls like Merlin and Achol, who share their stories, below.

'I want to be a doctor'

Merlin is a shy and reserved 16-year-old student at an orphanage and primary school in Juba. In a country where cultural conservatism often steers girls away from education, let alone studying medicine, her shyness masks a steely resolve to become a doctor.

“When my aunt fell sick, she was taken to a clinic where she later died because of poor medical care,” says Merlin. “It was then that I decided to study to become a doctor and save people’s lives.”

Her aunt’s four children were orphaned and now live with Merlin and her family.

“My cousins would not have been orphaned if their mother had had access to proper medical care,” she says. Merlin’s father is very supportive of her career ambitions. “I know many girls who end up married early because their fathers marry them off to obtain a dowry,” she says.

“My dad is unique. He gives my brothers and I equal support and is impressed by my performance in school.”

And Merlin is not the only girl in South Sudan with an eye on a career in the sciences.

'I want to be the family engineer'

An 18-year-old student at the Muniki East primary school in Juba, Achol is very clear on her career aspirations.

“In our family, we have doctors and lawyers, but no one is an engineer,” she says. “I want to be the family engineer.”

The fifth of 12 siblings, she sees only male engineers in a country where development and construction are on the rise.

“A woman’s eye for detail makes us ideal for engineering,” says Achol. “But it puzzles me to see only men on construction sites and I want to be the female on the construction site.”

Achol’s father is also supportive of her career choice and she has a message for parents who marry off their daughters before they finish school: “It’s awkward to make young girls carry the burden of marriage and if you support your daughter through school, she will be your pride in the future.”

Keeping girls in school

As an additional incentive to encourage school attendance, WFP provides 8,000 girls in 64 schools with monthly take-home food rations consisting of 10kg of cereals and 3.5 litres of vegetable oil.

To qualify, girls must be enrolled in school and attending grades 3 to 8, the stage when evidence shows they are at most risk of dropping out of school. They must also attend at least 80 percent of classes to receive the food.

“Since pupils started receiving school meals, we have seen improved performance in national examinations,” says Mary Santo Lado, headteacher at Mayo girls primary school in Juba.

“Despite the disruption caused by COVID-19, we are still hoping for excellent results.”

In March 2020, WFP’s school feeding programme was put on hold when schools were closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

As children in South Sudan await the re-opening of schools, WFP is mitigating against the impact of the pandemic on children’s health and nutrition by providing take-home rations for 23,000 children in the most food-insecure counties.

WFP’s school feeding programme in South Sudan is supported by generous funding from the governments of China and Japan, the European Commission Directorate-General for International Cooperation and Development (DG DEVCO), the German Agency for International Cooperation, KFW, the German Development Bank, and USAID’s Bureau of Humanitarian Assistance.