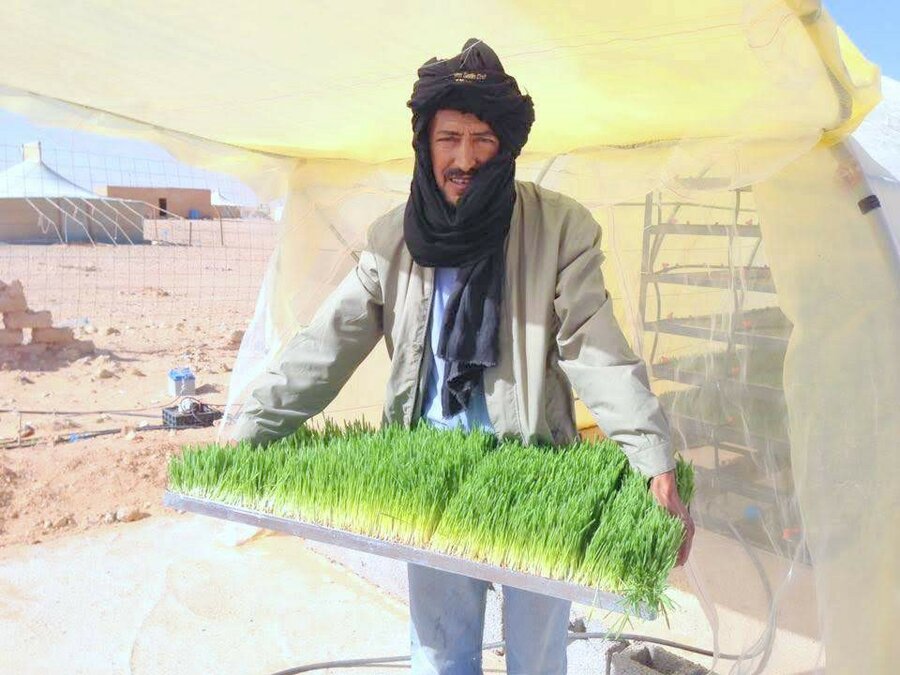

How I grew barley in the desert

"When I started, most people thought I was crazy, even my colleagues. Other engineers told me that it wasn't going to succeed."

Taleb Brahim reflects on the deep scepticism that greeted his plans for growing barley in the middle of the desert. Those doubts were understandable — Taleb's plan for agricultural production could barely have been more challenging.

The Sahrawi refugee camps are set amidst the sprawling, arid desert of west Algeria, where rainfall is as rare as sandstorms are common. Summer temperatures can soar to 49 degrees Celsius, and drop to below 35 in the winter.

Taleb knows this from first-hand experience. His family arrived here in 1975 when he was just 6 years old, fleeing like thousands of others from violence in Western Sahara. He grew up there with a brother, four sisters and his parents.

The unresolved conflict means the five camps near Tindouf town represent the world's most protracted refugee crisis.

Given the unforgiving environment, refugees were dependent on international assistance. The livestock on which families also relied fed on garbage and scraps, which meant the meat or milk they produced was lower quality and could make people ill. Malnutrition and anaemia remain common today, with many families struggling to secure a healthy, nutritious diet.

Even if families like Taleb's had enjoyed the right conditions to grow food or fodder, they wouldn't have known how to do it. "We are originally nomads, we did not have an agricultural background or the means to survive — the only possibility was to receive aid," he explains. "As Sahrawis, we have been experiencing life as refugees for the past 40 years. We know what it means to be a refugee, to be dependent on others for support.

"After a while, we felt that as human beings, neither our dignity nor the way we wanted to raise our children allowed us to continue to be constantly dependent on others."

Taleb had a route out though, securing a scholarship at Tishreen University in Lathiqiyahin, Western Syria, where he studied agriculture.

"It was so sad because I [was] away from my family. But that was the price I needed to pay in order to be educated," Taleb recalls.

When he returned to the camp in 1996 after graduating, Taleb was determined to use his education to change the landscape for his family and many others like them.

"My main interest focuses on small-scale agriculture, like home gardens and household livestock," he says. "We tried to meet the food needs of our people in a traditional way, through agriculture, but it wasn't enough. So that's what made me think of another approach, another solution, that could solve our problems.

"An American friend sent me a YouTube video about high-tech hydroponics for the production of green fodder, which allows you to grow fresh fodder without soil, using 90 percent less water and no fertilizers, in only a few days."

It was around this time that the World Food Programme (WFP) — who had been providing food assistance to the refugees since 1986 — also contacted Taleb. "I was visited by someone who asked for innovative project ideas to help refugees produce any kind of fresh food. She came at the right time."

Taleb presented his idea to the agency's Munich-based Innovation Accelerator in March 2017, where it was selected for development from among several other contenders.

WFP staff in Algeria worked with Taleb, the Innovation Accelerator and Oxfam to test an approach known as H2Grow hydroponics. A high-tech prototype, running off electricity and solar power, was scaled down into a cheaper, low-tech unit built with local materials which is easy to repair and replicate.

With this method, barley plants receive nutrients from solutions rather than soil, developing up to twice as fast as in traditional farming and using 90 percent less water. There are now 250 units of various sizes, through which 1,200 refugees have been trained to grow barley in just seven days to feed their livestock, with no additional materials like fertilizer or pesticides.

The hydroponic units can be fuelled by solar energy. Plants are stored in containers, greenhouses or mud-brick houses to shield them from the sun. Light, temperature and water supply can be more precisely controlled and monitored than for plants growing in soil.

Algeria was the first place hydroponics was used by humanitarian organizations in the Middle East and North Africa countries where WFP works.

With proper fodder, the goats are producing meat and milk, which in turn provide incomes and better and more nutritious diets for people.

More than this, the initiative is now very much locally owned.

"The training was conducted by refugee trainers who received their own training during the project," explains Taleb. "The units were also manufactured in the camps by refugees. It has become a project that is created by refugees, implemented by refugees, and that benefits refugees.

"Hundreds of families are now able to produce fresh fodder for their animals. What I thought could be a solution for my own animals has become a solution for a whole community. And for other communities too, since anything that can be adapted to these extreme conditions can be easily replicated elsewhere in the world."

Taleb has been working on this very goal over the past two years, with H2Grow hydroponics now in use also in Algeria, Chad, Jordan and Peru. Knowledge-sharing between refugees is proving invaluable in learning how the technology can be adapted to local conditions and people's needs. In Namibia, hydroponics is now a part of a school feeding programme supported by government partners.

"What makes me most happy about the project is when I see children, mothers, having fresh milk that they've never had before, when I see livestock eating healthily, and people can have their meat," says Taleb.

From the germ of an idea to a project growing across several countries, Taleb's efforts in conjunction with WFP and Oxfam were recognized in September 2019, when he was invited to discuss his work on the fringes of the UN General Assembly in New York. As member countries look at the best means to speed up progress towards achieving zero hunger by 2030, innovations like hydroponics will be critical.

And what about those who doubted him originally — they must see the results now too?

"Finally we did it, and I gained people's confidence and they believed in me," says Taleb. "I hope this project can meet people's needs, especially those who are living in extreme conditions. I live in the desert, which is the result of climate change, of desertification. This is a solution that can help people, or prepare them to be ready for these types of conditions.

"I hope we can reach these people, and we can raise funds to cover the costs. I hope that soon I'll start a system of hydroponics in which we can produce different products, fish, meat, eggs, all the needs of a family in one system that saves water."

You can read more about H2Grow here.

— Story by Paul Anthem and Cassandra Prena.