First person: ‘What I saw after the Indian Ocean tsunami took me years to process’

The Indian Ocean tsunami of 26 December 2004 – unleashed by an earthquake off the coast of Indonesia measuring 9.1 on the Richter scale – triggered the “most complex and wide-reaching emergency operations ever mounted” by WFP. The Tsunami also struck the Maldives, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand and even Somalia. Entire coastal communities were wiped out and an estimated 228,000 people were killed. Banda Aceh, in Indonesia, was the epicentre of devastation. Below, WFP photographer Rein Skullerud recalls heart-wrenching scenes after flying into the city, as the world rallied to help survivors.

I arrived in Banda Aceh on 3 January 2005 – a week after it struck on 26 December 2004. I flew from Rome to Jakarta and then to the island of Sumatra. A landing strip had been cleared – and there was a cow in the middle of it when we landed. Really close call.

This was the biggest humanitarian response. It felt like being in the Vietnam War – choppers flying all over the place, going to pick up people cut off on small islands, people who had lost everything and needed to get to safety. Entire villages were destroyed.

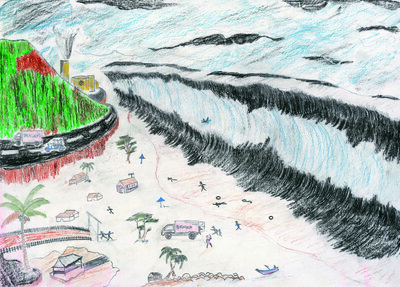

Banda Aceh was where people would come and sell their crops and goods. All of that had fallen to pieces, the economy was in tatters. The fishing community was destroyed. Boats had landed all over the place. The city has mountains all around it and faces the sea. The water just ran around the mountains and then went into the sea again, destroying virtually everything in its path.

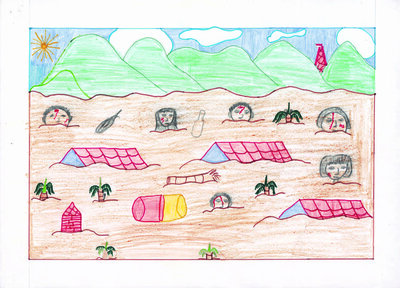

One photo was published all over the world: little squares in the ground, all that remained of the bases of houses. A mosque was the only thing that survived. People went and took shelter there because they thought it was God’s will that had saved the mosque. It’s all rice paddies now because no one dares to build there anymore.

My biggest shock was all the dead bodies, everywhere. Some were stuck in trees. Teams retrieving bodies took weeks to take out one stuck in water outside our makeshift office near the airport.

I spent 45 days there living in a tent. By the time I left, they were still pulling out 1,000 bodies a day. Most of my photos from that time are too graphic to publish. I had nightmares every night…until I went back to mark a decade since the tsunami. That’s when the nightmares ended.

One thing that struck me when I returned in 2014 – as a father – was the children. In 2004, children’s eyes, in just one day, had become the eyes of adults – sad eyes. But when I went back, and I felt a desperate urge to go back, it was heartwarming to see that joy had returned.

Sailing into the tsunami

Then there was this guy, Surya Darma, a fisherman. He told me he was out at sea in his large fishing boat when he saw the tsunami approaching. He had to make a split-second decision whether to rush back, because his family was ashore, or to go further out at sea – which is the logical thing to do if a tsunami arrives (the deeper the water, the safer you are).

He faced the tsunami head-on and used his boat to climb the wave. He was quite emotional as he was telling me all this. He and his crew “weren’t even sure we were going to manage to overcome the peak,” he said. “And then when it hit the land, we rushed back to go and see what had happened to our families.” Luckily, his family survived. But the incredible thing was that moment when he was devastated because he had to make the decision: “Do I head outwards and I know I will survive, or do I head back to shore trying to save my family?”

They’ve since built several concrete buildings along the shoreline that are supposed to withstand the impact of a tsunami. There’s one every so many hundred metres, so that if another tsunami comes, people can go and seek refuge up on top.

In 31 years with the World Food Programme, witnessing conflicts, disasters and extreme weather events such as the quakes Haiti and Pakistan, the conflicts in Mali and the Central African Republic, floods in Pakistan and the endless drought in West Africa, my experience in Banda Aceh was one of the most harrowing.

Over the years, I said, “You’ll become better, you’ll become harder and be able to withstand these situations and witness them with more strength.” For me, it hasn’t been that way. For me, it’s gone the other way around.

Now, if I head out to an emergency, there can be a situation where I just can’t take pictures because I need to help physically. I’ve spent hours helping to offload rice off a truck because I thought it made more sense for me to do that in the minds of the people I was with.

A look at how WFP is braced for future shocks

“Events are coming faster and faster, and rapid financing is critical to ensuring timely action,” says Jesse Mason, WFP’s senior adviser on climate early warnings and anticipatory action. “Building capacity and improving early warning systems – knowing when emergencies like La Niña or El Niño are coming – is only half the battle. We’re advocating for pre-arranged financing that can be triggered within hours, weeks and sometimes months before an extreme weather event has occurred – not weeks or months after a humanitarian disaster.”

“Where it’s possible, seeing hazards before they become humanitarian disasters by getting people out of harm’s way is key to providing cash grants and food supplies to cushion the blow once they arrive,” says Mason.

Going into 2025, WFP’s focus on “anticipate, adapt, restore, and protect” informs our work with governments, and we are taking note of every lesson the next emergency-response offers.