Drones take flight to help end hunger

If the World Food Programme were a neighbourhood, the agency's drone pioneers would be the teenage kids.

Their speech is nothing like their elders'. No talk of leveraging this, strategizing that. They don't actually sit together: their voices come to me from Thailand, Germany and Panama. Culturally, though, they hang out on the same street corner.

Or maybe in the school lab.

"Flying a drone is like being a diver," says leader of the pack Haidar Baqir. The IT engineer launched WFP's drones-against-hunger project. "You get to see things others don't. Like having a third eye."

Baqir has just landed back in his home station of Bangkok. The long flight from Mozambique, with 14 hours' delay in Nairobi, hasn't punched out his lights. He's brightly discursive as he tells how he's completed the last of four workshops (all Belgian-funded) on the use of drones — or UAVs, short for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles.

"Mozambique is an ideal environment for testing the ground — or the air, as it were. It's flood-prone, not a conflict zone, and the disaster-management authorities are on board."

Floods. Quakes. Hurricanes. When disaster strikes, rivers change course. Roads splinter. Houses cave in. Communities are chewed up, hit sideways, washed away. How do you tell who's where? Where do you run power lines? How do you tell who's hungry?

Drones, I'm beginning to see, are a cheap, efficient way of reading the lay of the land when the ground has shifted.

In the Mozambican field exercise, the small winged device circles above parked trucks before homing back into expert hands, like a hawk elegantly rejoining its master.

But then, that's the easy bit. Comparatively speaking.

"The hard part," Baqir tells me," is to arrive at a global regulatory regime that allows us to fly our kit safely, reliably and effectively."

Hence working groups within working groups, at WFP and in the wider UN system. They've been set up to hammer out just that: the macro settings of UAV deployment in humanitarian emergencies.

For instance: What does it take to assuage the fear, among some governments, that drones can be used for espionage? It's a cold-war tinged concern — but also, what with angst over mass surveillance and data dumping, one that's blisteringly contemporary.

HUMANITARIAN_UAV.mp4

Resistance to UAVs is both diffuse and diverse — legal, security-linked, privacy-based or else a mash-up of anxieties. It may blend the commercial and the political, as it has in Nepal.

"After the earthquake of 2015, everyone was at it," says Gabriela Alvarado, a Panama-based colleague of Baqir's and self-described natural born geek. "So many drones in the sky… Eventually the Nepalese government shut it all down: they worried the pictures of destruction would damage their tourist industry."

A drone pilot herself, Alvarado talks movingly of shooting footage in Dominica with a friend from Ericsson Response, a humanitarian telecoms service, after hurricanes Irma and Maria.

"As we were live-streaming our UAV pictures, we saw a car perched on a rooftop. We were high up on the island, there were no roads in the vicinity, and yet that car had somehow landed on that house. And I pictured myself and my children in that house, in that car, and the vulnerability of all of us in the face of disaster just leapt out at me…"

In Peru, a WFP simulation Alvarado was involved with missed 2017's floods by a few months: there was little opportunity to observe the immediate aftermath. Then again, on the regulatory side, the team found a government convinced that using drones in disaster responses is squarely a good thing.

"In the Dominican Republic too," Alvarado says, "the civil aviation authorities were very open."

But open though governments may be, few nations — Baqir names Australia and the US among them — have a satisfactory regulatory framework in place.

Nor does the absence of regulation mean UAVs have the run of the sky. On the contrary: it can mean drones are locked out altogether — the tech equivalent of recognizing a fine painting, but cellaring it for lack of the right frame.

"We took our drone to Uganda," says Jonathan Dumont, a long-time TV producer who runs WFP's video department. "At the airport, the customs people saw it on the x-ray. They were very apologetic and said: ‘We know you're authorized to film here and this is just a tripod in the sky. But our Ministry of Aviation have put a hold on these things because they haven't decided the rules to follow.' So they took it away."

On his way out of Uganda, Dumont was ushered into a room at Entebbe airport and told to collect his device. "There were hundreds of drones in there. I had trouble recognizing mine. That's when I thought I should upgrade."

He now has. His latest UAV — a Chinese-made Mavic Pro — is hardly larger than a Frisbee. By making drones barely detectable, the industry may end up defeating the bans and near-bans: nothing makes bureaucracy obsolete so much as miniaturization.

One way or another, Dumont has been using UAVs to films emergency crises and disaster zones for years. His recent pictures of the Rohingya camp at Kutupalong in Bangladesh are what you might expect from Sebastião Salgado, the Brazilian photographer with an anthropologist's eye, if he shot in colour and from the air: they share that sense of tidal humanity, that strangely ordered syntax of epic plight.

Drone pictures have a dual role at WFP. They function both as raw visuals for emotional impact and (this should soon happen in earnest) as a data source for operational analysis.

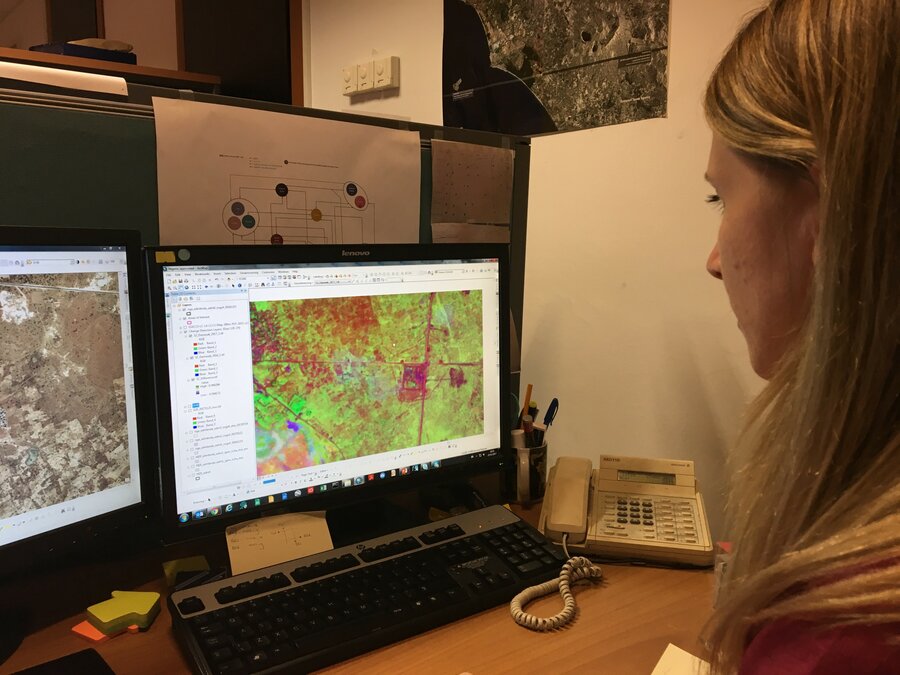

"I'm working on how to integrate UAV pictures with satellite imagery," says Sarah Muir matter-of-factly, as if it were a question of folding in the egg whites just right.

Drones can't replace satellites, she explains. Yet they're great at filling the knowledge gaps.

"Cloudy and unsettled weather — say, just after a hurricane — can make satellite imagery unusable. But UAVs fly below the clouds. Then there's the benefit of precision — from the 10 metres you get with satellites, down to just two or three centimetres with a drone."

And where satellite imagery can take a week or more to extract, drone video is available in a heartbeat.

All in all, splicing together both sets of pictures will allow Muir to make extraordinarily sharp inferences, from Rome, about the state of crops, of animals, of people half a world away. These extraordinarily sharp inferences she will then turn into extraordinarily zoom-able maps, a blueprint for much smarter aid responses.

But data doesn't interpret itself. It takes a remote sensing analyst like Muir to breathe meaning into it.

That, or a machine.

"We thought, all this interpretive stuff — counting the houses, deducting things from the roof damage on them, extrapolating demographic data — why do it manually? Why not have it done by Artificial Intelligence?"

Jamie Green's voice comes down the line from Munich. A tech start-up founder, Green now works at WFP's Innovation Accelerator, an improbable extension of the UN agency.

The Accelerator's role is to do exactly what UN agencies don't: race through administrative procedures; take a wildly speculative approach to things; trial stuff quickly and junk it if it doesn't work.

It is the id to WFP's ego. And it's is now collaborating with private research institutes, as it looks to automate the interpretation of UAV imagery.

So — some sort of enhanced analytical software?

"Exactly," Green says. "In two stages. First, you train the software, using thousands of images. This would take place on powerful computers in the cloud. Then, ultimately, you'd get something to run on a laptop in the field — reading UAV pictures in real time, with no internet."

Back in Rome, I ask Muir, the remote analyst, if she's worried that Green's A.I. activism will do her out of a job.

She thinks a little, then shrugs, then smiles.

"You still need to tell the machine what to look for," she tells me. "I've got a few days yet."