Democratic Republic of Congo battles Ebola alongside coronavirus

As the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) grapples with the coronavirus pandemic and a deadly measles epidemic, it is also facing its 11th eruption of Ebola — having barely seen off its tenth.

Ebola is a viral haemorrhagic fever, first identified in 1976, close to the river from which it takes its name. Transmission is via the bodily fluids of an infected person. In recent outbreaks, roughly two-thirds of those who contracted it have died.

"Even by the standards of the DRC, this is quite challenging," says Susana Rico, World Food Programme (WFP) Ebola Response Coordinator for DRC. "Addressing rising demands will surely be a herculean task for all concerned."

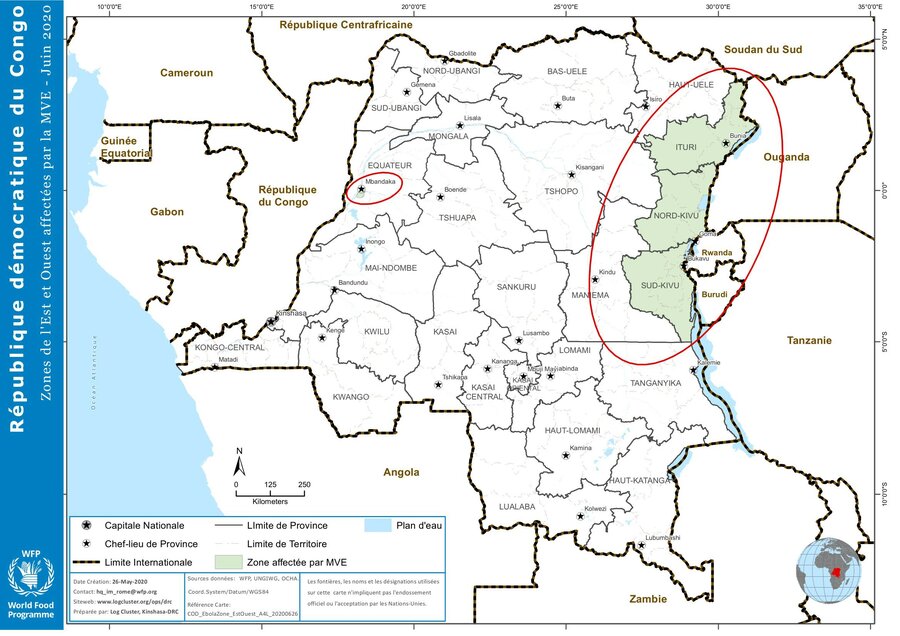

The current Ebola epidemic affects the northwestern province of Équateur, a zone of equatorial forest along the Congo river, which was hit by the ninth epidemic in 2018. Mbandaka, the epicentre of the new outbreak, in which 24 cases and 13 deaths have so far been registered, is a busy port, some 700 km upriver from Kinshasa. Getting there by boat from the capital takes more than a week.

While the Équateur outbreak has generated relatively few infections so far, experts are concerned that five health zones — Mbandaka, Wangata, Bikoro, Bolomba and Iboko — have been hit. Confirmed cases are reported in villages several hundred kilometres from Mbandaka, making access for health workers very difficult.

Équateur province has only 45 km of paved road. The DRC as a whole, despite being three-and-a-half times the size of Texas, has only some 6,000 km of road — and only 20 percent of that is paved.

The WFP-run UN Humanitarian Air Service, better known as UNHAS, has increased the number of flights into Mbandaka from both Kinshasa and Goma, enabling health workers to access the zone.

The new epidemic hit just weeks before the tenth — the second-largest globally after the 2014–2016 West Africa epidemic which killed 11,310 people — was officially declared over on 25 June. Concentrated in the eastern provinces of Nord Kivu and Ituri, it resulted in more than 3,400 cases and 2,200 deaths. That was the first Ebola outbreak in an active conflict zone.

Now, in view of the increase in the number of cases in remote villages in Équateur, UNHAS plans to deploy to Mbandaka the MI-8 transport helicopter that was based in Goma, the largest city in eastern DRC, throughout the tenth epidemic.

"With a helicopter in the area, we'll be able to reach remote places in two hours rather than two days," says Geoffrey Mwangi, WFP's Chief Aviation Officer in the DRC.

Official figures suggest there are 6,000 cases of COVID-19 infection in DRC, but the real number is likely much higher given limited testing capacity — this means that a raft of measures are in place to ensure that Ebola responders do not carry that disease into Équateur. All UNHAS passengers, staff and crew wear masks and surgical gloves and observe social distancing. Passengers have their temperatures taken before boarding.

During the previous outbreak in Équateur in 2018, WFP's role consisted mainly of logistical support to the medical response led by the government and the World Health Organisation (WHO). The approach to the recent epidemic in the east was two-pronged: logistics and air transport for the entire response, and the provision of food and nutrition assistance.

In the almost two years of that epidemic, UNHAS ferried more than 46,000 responders, and light cargo, into and around the affected area, using helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft.

The air links enabled responders to quickly reach places dangerous and time-consuming — if not impossible — to access by road.

WFP also supported WHO with warehousing services and the management of essential items such as Personal Protective Equipment.

Given the considerable scale of the recent epidemic in the east, WFP also distributed food and nutrition assistance to affected communities, an approach that contributed to both containment and "contact" tracing.

People who had been in contact with Ebola sufferers were given a weekly supply of food for four weeks, corresponding to the period of their medical observation. This meant that they no longer needed to go to their fields or to market in search of food, limiting the spread of the disease.

WFP also assisted people who came forward for testing, encouraging others to do the same and help identify infected individuals.

In areas where there was mistrust with regard to the Ebola response, the availability of food assistance made that response more acceptable.

WFP would like to thank USAID's Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance, ECHO, Canada, UN CERF & Germany for making the Ebola response possible.