Cassava at the crossroads in Congo

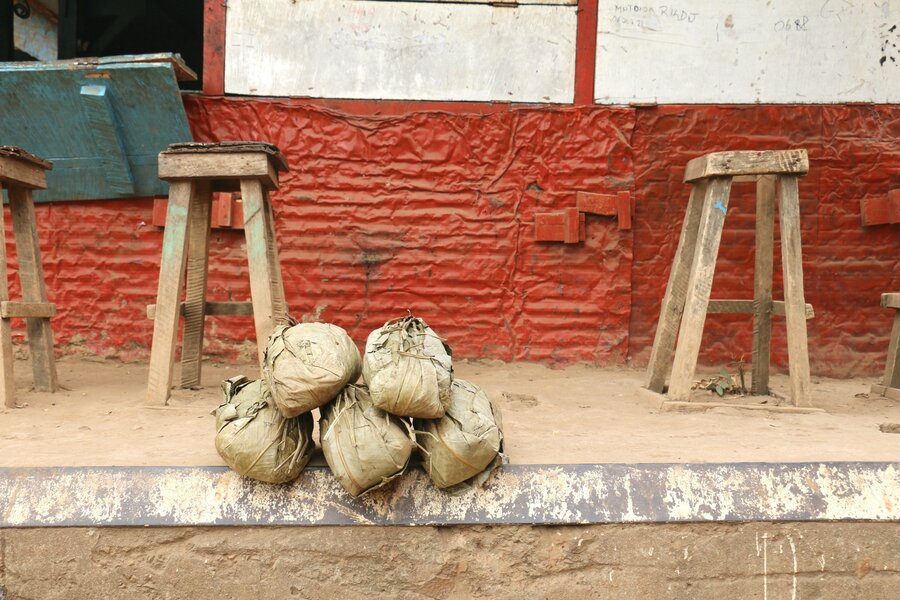

"Cassava is the main dish for the people of Congo, everyone in Congo eats cassava," says Brigitte, a chikwangue vendor in the southern town of Loudima. Chikwangue, a ubiquitous street food, is a fermented cassava loaf wrapped in leaves. "Without cassava we cannot eat well," she adds.

It's no wonder that the crop is Congo's undisputed number one food. Cassava paste, served with a side of saka-saka — pounded fresh cassava leaves — is the national dish. Its popularity secures cassava's place as the cornerstone of Congo's food system.

Versatile but neglected

First brought to Congo from South America in the 16th century, cassava comes in an array of sweet or bitter varieties. In urban areas, people tend to prefer a fermented cassava porridge called foufou, or thick slices of chikwangue, the steamed cassava loaves that street vendors sell wrapped and ready to eat.

But the crop's development is at a crossroads. Cassava is susceptible to the mosaic virus, a devastating disease that causes huge losses for farmers. "Every family grows cassava," explains Bernard Dihoulou, WFP's field monitor in the highly productive Bouenza region. "Cassava sales are the very lifeblood of these communities, it is how people pay for school fees," he adds. According to FAO, Congo produces over 1,5 million metric tons of cassava every year.

Household cassava-processing is a labour-intensive task that seems to keep women busy at all hours of the day. The division of labour for cassava reflects longstanding gender norms and roles: men tend to be involved in production, while women process cassava at home, and sell it on the market.

The most common processing methods, however, deprive cassava paste of key properties, making it nutritionally poor. And on urban markets, the food faces competition from cheap imported wheat products.

As Congo works to diversify its economy and build an agricultural system capable of feeding the nation, it is time to step up support for the cassava value chain. A combination of approaches — from industrial to artisanal — can help reach this goal.

Untapped potential

Thanks to technical assistance from FAO, IFAD and China over the past ten years, farmers now use healthy, mosaic-resistant cassava cuttings and productivity levels are rising. Unfortunately, processing is largely traditional and home-based — not of the scale needed to absorb growing surpluses, and insufficient to meet expanding urban demand. Home-produced cassava products tend to be relatively expensive.

Cassava has untapped potential as a commercial crop: it happens to be a great source of starch for a range of food and industrial applications. In Latin America and Asia, integrated cassava mills produce everything from glue to instant noodles and biscuits.

A thriving Congolese cassava industry would absorb surpluses and offer consumers a choice of relatively cheap, quality, locally made products. There is also potential to fortify cassava in an industrial mill, which could help ensure children receive essential nutrients when they have their daily helping of cassava.

Supporting cooperatives

Small producers are also tapping into the growing market for cassava products. The Yamba district of southern Congo is home to a unique cassava processing cluster. Back in 1952 a man from Yamba travelled to Benin where he learned how to process cassava into gari, a toasted cassava flour. When he got back home, he shared the knowledge with his community. Ever since, the people of Yamba have been processing cassava into gari, which they sell as far as Pointe Noire, Congo's second city on the South Atlantic coast, and even Libreville in Gabon.

It's back-breaking work: first people peel then soak cassava tubers. They then grate the tubers on an arched, perforated metal sheet.

The grated cassava is pressed in bags under a large pile of rocks for two days. Workers then sieve and toast the resulting cassava flour on a metal sheet placed over an open fire.

Gari produced in this way is good quality, but the process can be improved. Producers risk injury and smoke inhalation. "My back hurts after a day's work lifting stones," says Angèle, a middle-aged cooperative member. "And our eyes sting from the smoke". The valuable starch is lost at the pressing stage.

Thankfully, many of these issues have been resolved in West Africa through improved machinery. Cassava producers in Congo are looking forward to promoting exchange with West Africans to give a boost to Congo's emerging craft cassava producers.