Behind the scenes: humanitarian airdrops in South Sudan

In the most inaccessible parts of South Sudan, cut off by conflict, insecurity and poor infrastructure, the sight of orange parachutes raining down from the sky is a welcome one. It means World Food Programme (WFP) planes are dropping much-needed food that could not otherwise reach people often living through famine-like conditions.

Airdrops require extreme precision, detailed and up-to-minute information, steel nerves and artful skills at the time of delivery. But where does it all start?

Recently I visited the WFP warehouse in Adama, central Ethiopia, where all the behind-the-scenes work happens.

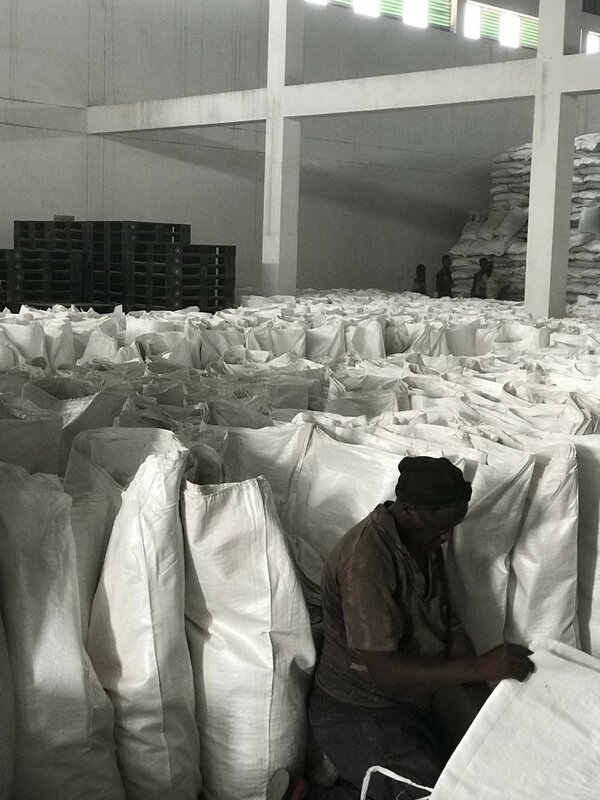

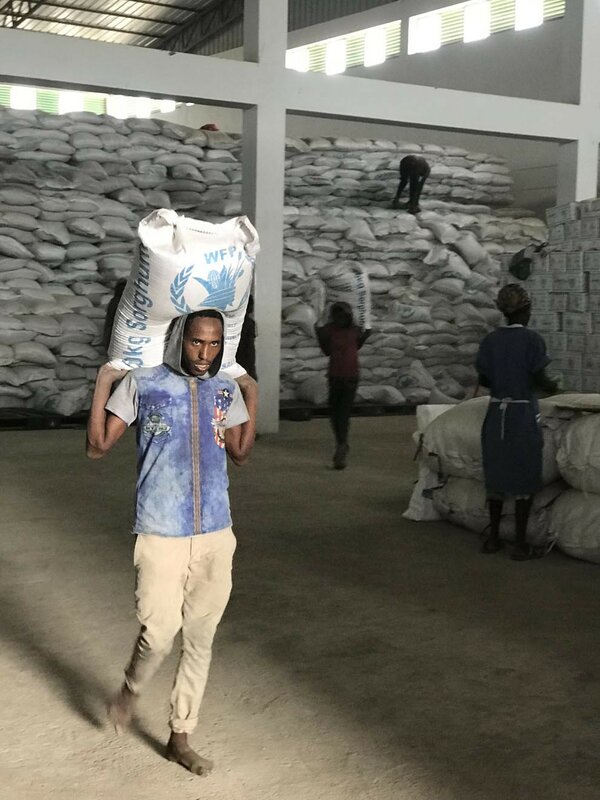

The first thing that you notice about the warehouse is the sheer size of it— 8,000 sq m — that's one-and-a-half American football fields. Looking around, you realize you are surrounded everywhere by bags of sorghum — thousands and thousands of bags of sorghum. And as you walk in, you find yourself moving along a small path among what looks like huge pieces of crumpled up paper. It isn't of course. It's bags being prepared for airdrops.

Across the warehouse, men and women are working fervently to prepare these bags for an airdrop. Zeff Kapoor is Head of the WFP office in Adama, and Chiara Camassa is the Logistics Officer who is responsible for the South Sudan operation. We talk about the details of the operation:

What are these people doing? What goes into preparing these bags?

Zeff: On any given day, there are up to 400 men and women working in the warehouse, getting the food ready for a drop. 50 kg bags of sorghum are opened and poured into a 90 kg bag that is then reinforced with another five bags for extra resistance. Each layer is sewn together with the next, starting on the inside, using a handheld stitching machine. The team averages 5,000 bags a day, which is about 250 metric tons (mt) of food. The same process is used for pulses — only the colour of the final bag is different: white for sorghum, red for pulses.

What are the blue bags for?

Zeff: These are the specialized nutritious foods that WFP distributes. They have to be bundled because their packaging is designed to retain nutrients. Four sachets of 1.5 kg each are first bundled together in one 25 kg bag. Seven of these bundles go into one 90 kg bag that is then reinforced with a further six bags, again all stitched together one at a time. The last bag is blue, to differentiate it from the sorghum. On average, the team produces 2,000 of these bags a day, about 50 mt.

So what happens once the bags are ready?

Chiara: The team loads them onto trucks that will deliver them to our hubs in Gambella and Jimma. That's where the aircraft are. Two aircraft are positioned in each hub. Each aircraft does a morning and an afternoon rotation, on average dropping 240 mt per day. The afternoon drops must be lighter due to weather constraints.

What does an average day look like?

Chiara: We spend our day keeping this operation moving. We must make sure there is a steady flow of commodities, and we are constantly on the phone making sure that customs requirements are met and that we have all the relevant authorizations. Of course, we are also coordinating with the team on the ground in South Sudan to make sure everything is in order on that side and that they are ready for the drop.

Story by Annette Angeletti

Learn more about WFP's work in South Sudan.

In partnership with Amcor, one of the largest global packaging corporations in the world, WFP is constantly working to optimize packaging to reduce the loss of food, streamline operations, save costs and reduce environmental impact so that we can save and change more lives.