The backstory: Malawi school delivers fresh food – and lessons on learning

Walking into Felix Malinda’s office at Namilongo primary school, in southern Malawi, felt like stepping into a different world. There was no technology in sight – just posters and papers covering the walls and Malinda's wooden desk.

The only cutting-edge equipment around were my cameras, capturing images of the school, its teachers and students – and recording a World Food Programme (WFP) colleague interviewing Malinda. Sharply dressed in a grey suit and striped tie, the headteacher described his deep esteem for his students and fellow teachers.

Hand-drawn posters were plastered across his large, airy office, listing projects like a ‘school improvement plan,’ and reminders that ‘vulnerable children have a right to education.' It felt like a space where students and teachers shared a mutual sense of responsibility and respect.

WFP partners with Malawi primary schools like Namilongo to buy the ingredients for school meals from local farmers. It’s a win-win for the entire community. Students benefit from fresh, nutritious meals. Farmers benefit from steady clients for their fruits, vegetables and legumes. Parents – many of them farmers – know their children are attending schools that feed both stomachs and minds.

Findings show WFP’s school meals programme in Malawi helps reduce absenteeism and increases attendance. But the potential windfalls are much bigger: producing returns on investments in areas ranging from local economies, to health and gender equality. That’s key for Malawi, one of the world’s poorest countries, where more than 5 million people are food insecure. Extreme weather, including an El Niño-sparked drought this past year, has hit smallholder farmers – who account for 80 percent of the population.

“In the past, our learners would drop out of school because of various reasons, including poverty and hunger,” headteacher Malinda said. That’s stopped, he added, since the locally sourced meals programme, “and we have noticed that the school’s enrolment is growing.”

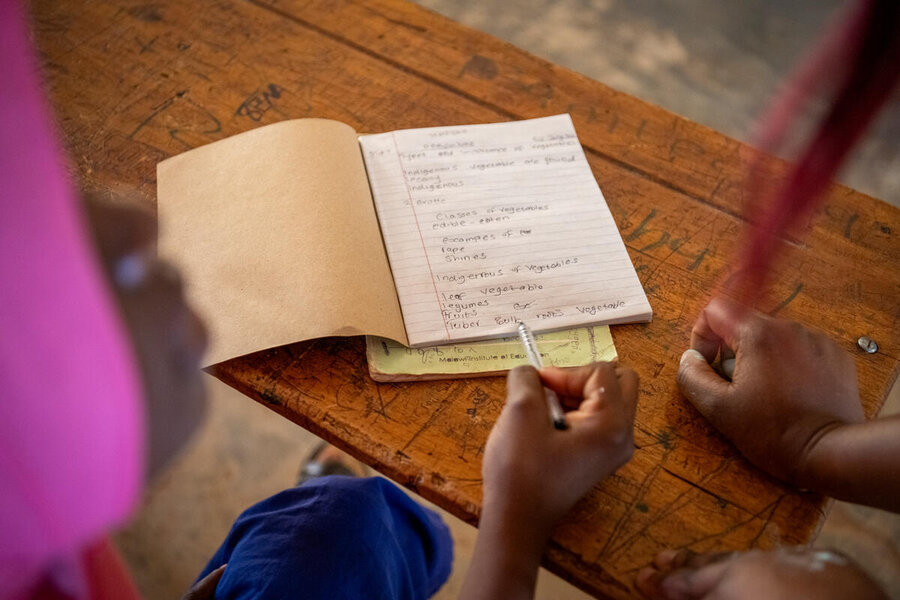

Filming Malinda was my last task of the day. I had spent the morning photographing his students eating a WFP-supported breakfast of porridge, and captured images of an English grammar lesson. I focused on a 14-year-old girl called Hapsa, who was about the same age as my daughter.

“My children are benefiting from this project because their nutrition status has improved and I’m able to buy them clothes,” said Hapsa’s mother, Matrida Chikoko, one of the farmers supplying produce to Namilongo. Her two boys also attend the primary school.

“They eat breakfast every day at school,” Chikoko added. “I observe healthy bodies in my children because they eat diversified food, whereas at home I used to feed them only nsima (maize meal) and relish (vegetable sauce).”

I still think about Hapsa, who is about the same age as my own daughter. What kind of life would we have, had my family been born in Malawi? I imagine my own daughter attending Namilongo primary school – and how its values of care, respect, and education would make any parent proud.