From Afghanistan to Venezuela and everything in between – the journey of a committed humanitarian

“With Afghanistan, it was love at first sight.” Susana Rico, a World Food Programme (WFP) veteran who is now heading the organization’s newly opened office in Venezuela, recalls the days when she landed in Kabul on her first field assignment, as Deputy Country Director. It was 2002 and a new government was being formed. When asked what made her fall in love, Rico is adamant: “It’s the resilience of the people. Even after 20 years of war, they still had hope.”

As she stepped off the plane, still on the airport tarmac, she was told she would be officer in charge as the Country Director was away. “It did not hit me,” Rico says, “I just took it one day at a time.” Finding herself in charge of WFP’s largest operation at the time, with 1,200 staff, 600 trucks and an extremely complex pipeline – further complicated by a tortuous road network and infrastructure shattered by two decades of war – was not easy. “My learning curve was like climbing a grease pole,” she says, laughing.

But years of poring over documents in her role at the organization’s Executive Board meant she “knew every policy, every mechanism”. That, combined with support from long-serving staff, meant she quickly got to grips with the ins and outs of the operation.

“What I am most proud of is the impact we had on education,” Rico says. As schools started to open up to girls, WFP started giving their parents a can of oil as an extra incentive on top of the regular 50 kg bag of wheat handed out to all schoolchildren. “In a country where the birth of boys was celebrated while girls were considered a burden, this started making girls valuable.” It was a small, incremental paradigm shift. “Families would see the financial benefit of educating their girls, who, as a result, would learn to read and write.”

Having previously worked in the Population Division in the UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Rico knew that this could set off a virtuous circle. “The education of girls is a determinant factor for a country’s development,” she explains. “A girl who has an education is a powerful tool for change. She will likely have fewer children, and fewer children means they’ll have better chances of surviving and better prospects in life. By the third year of doing this, you can really change a country’s demography – and we were making this happen in Afghanistan.”

I had a UN career – and then I became a humanitarian

It can only be hoped that the progress made was not in vain, given latest developments in the country and concerns for its future. WFP continues to deliver across all 34 Afghan provinces despite the challenges.

Rico was not a natural born humanitarian. She joined the UN in New York as a typist at the age of 28 to pay her way through college. “I was a very good typist,” she jokes – her trademark laughter, which she describes as her “resilience mechanism”, breaking out again. Her work, her studies and her inquisitive mind set her off on a UN career. “But it was only after I joined WFP and learned about its work that I became a humanitarian.”

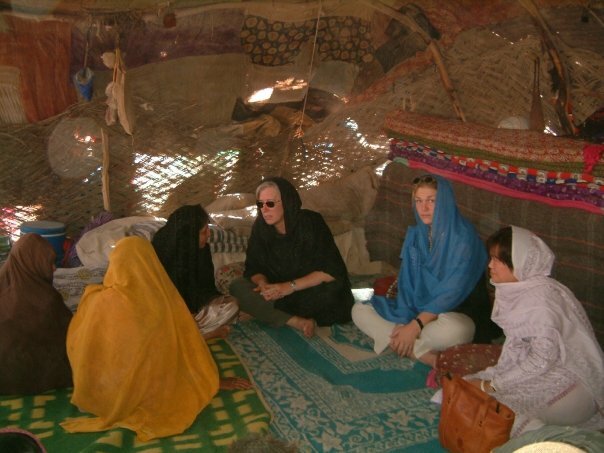

After leaving Afghanistan – “I would have stayed on another 10 years, if asked”, she says – Rico worked in a number of WFP programmes across different continents, including complex emergencies and conflict-torn countries.

Whether it is Afghanistan, Niger, the Democratic Republic of the Congo or her new duty station in Venezuela, “knowing that what you do is having an impact on people’s lives is a feeling that moves you from the gut,” she says. “You feel you can do things. You begin to see the areas where you can make a difference. And that’s an incredibly powerful motivator – to get up in the morning and know you can make somebody’s life better.”

Referencing the four principles that drive humanitarian action – humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence – she says: “To me, humanity is embedded in everything we do.” To these principles, Rico adds a special ingredient of her own: humility.

“We offer assistance, not impose it. We negotiate access, not demand it. Whether it’s governments or other parties, we must never come across as arrogant, as that creates frictions and can put our very colleagues at risk, especially in conflict situations. If you rub a war lord against the grain, you don’t know what the consequences might be,” she says.

As the anniversary of WFP’s Nobel Peace Prize approaches, Rico reflects on her experience in war-ravaged countries. “There are things we can do to improve the lives of people living through conflict. But the decision to start and feed those conflicts is well above their heads – and ours. Think of Afghanistan: the daily investment in warfare could surely have solved all the infrastructure, education, health and hunger problems,” she says.

“Even in the midst of war, however, people need to have a life. They even manage to find some kind of normalcy. And I just want for WFP to be able to help them.”